The following is the second in a series of three articles about two Scottish families who migrated to Australia in the 1850s and who settled eventually on the Mid North Coast of NSW.

Arriving in NSW

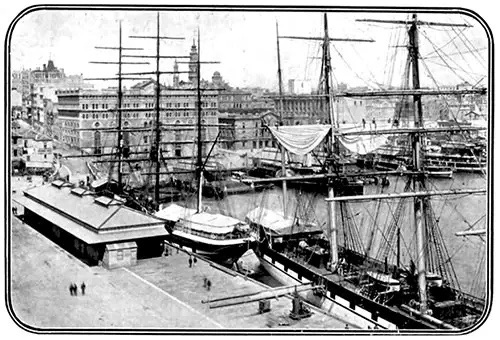

The Edward Oliver, carrying the Anderson family, sailed into springtime Sydney in November 1856; the Alfred, with the Ross siblings, arrived eight months later in the middle of the Antipodean winter of July 1857. The wharves of Sydney Cove might not have been as crowded as Liverpool, but they were busy and bustling just the same. The Andersons, and later the Rosses, disembarked to a brave new world, full of new sights, sounds and smells. What was Sydney like in 1856 and 1857?

A colony of the British Empire

Seventy years before the Andersons and Rosses arrived in Sydney there had been no city there at all, the beautiful harbour home rather to scattered groups of the Gadigal people of the Eora nation. Within a decade of the arrival of the first exiled convicts from Britain in 1788, free settlers had started coming in search of a new life in this “new” world. They joined a colony of convicts and soldiers, then, as time went on, ex-convicts and the offspring of the new arrivals, born free into this brave new land. During the first half of the 1800s the Australian Government started subsidising the passage of immigrants from Britain to swell the ranks of the fledgling settlements and as Sydney grew, the newcomers started pushing west, south and north into what had become known as New South Wales.

For the most part these newcomers had little respect for or interest in the existing inhabitants – the indigenous peoples – who they were willing to displace or destroy rather than get to know and understand. In that age of colonialism (which was only the latest of many which had come before) Europeans believed the world was theirs for the taking, with little regard for existing communities of people in the lands they had “discovered” on their voyages of exploration over preceding centuries. They had a firm belief in their own superiority, and expected indigenous peoples to believe that too. Their guns were certainly superior to the spears of the natives, but the most destructive weapon they brought was their diseases, which progressively decimated Aboriginal communities.

Even more devastating in the long run was the attitude of superiority they brought, the belief that they the invaders were somehow “better” than the local inhabitants and that it was their duty to make the locals like themselves, to save them from their ignorant and primitive ways. This concept, which we now call “racism” (a word unknown then), sadly persists to this day, and continues to cause injury and division wherever it is allowed to grow. Thankfully we are more aware of it now, but the human heart remains the same, and unless there is a heart change, the conflict will continue.

The Australian frontier wars, that followed the arrival of the convicts, soldiers and settlers, showed that the native inhabitants saw the newcomers not as superior, nor as saviours, but as “invaders.” They fought fiercely to defend their land, but by the mid nineteenth century they had been largely subdued, their millennia old way of life having been devastated by the weapons and diseases of the colonists. The Aboriginal peoples did not disappear, of course, and as invariably happens in such situations, there was much mixing of the races – between the British and the indigenous Australians – though this was frowned on by both sides and only grudgingly acknowledged. Sadly, the understandable and justified anger, the injury and pain, the tensions and mistrust that originated in those early days of conflict, still exist in many places in Australia today, complicated by the continuing arrival of immigrants from diverse cultures all over the world. When will the peoples of this land learn to live in peace and harmony together?

Sydney in the 1850s

The total population of Sydney in 1856 was around 53,300. Today Sydney numbers nearly 5.3 million, a hundred times bigger than when the Andersons arrived. It was, at that time, more akin to a large country town in present day Australia than to a city. Sydney town in the late 1850s was surrounded by a number of “rural hamlets” including Balmain, Camperdown, Canturbury, Chippendale, The Glebe, Newtown, O’Connell Town, Paddington, Redfern, St Leonards and Surrey Hills. These names are familiar to modern Sydneysiders (except perhaps O’Connell Town, which was near Newtown on the site of what is now Sydney University), though most of them are now inner city suburbs, rather than “hamlets” on the outskirts. Canterbury was a settlement in the west, St Leonards a tiny settlement on the northern side of the Harbour accessible only by boat, and Paddington formed the eastern edge of the “metropolis,” beyond which there were only bush tracks out to the cliffs of South Head. This collection of small communities was evolving into a city, but few would have imagined that the forest clad hills that spread north, south and west from Sydney cove would one day be covered by the city sprawl that is so familiar today.

The 1850s were wild days in the colony: gold had been discovered near Bathurst in 1851 by Edward Hargreaves, sparking a “rush” of people from all over the world who came to seek their fortunes. A contemporary observer described the city that greeted the Andersons when they arrived:

Sydney [had] assumed an entirely new aspect. The shop fronts put on quite new faces. Wares suited to the wants and tastes of general purchasers were thrust ignominiously out of sight and articles of outfit for goldmining only were displayed. Blue and red serge shirts, Californian hats, leathern belts, ‘real gold digging gloves’, mining boots, blankets white and scarlet, became show goods in the fashionable streets. The pavements were lumbered with picks, pans and pots; and the gold washing machine or Virginian ‘cradle’, hitherto a stranger to our eyes, became in two days a familiar household utensil, for scores of them were paraded for purchase… (Quoted in Sydney, p63, by Geoffrey Moorhouse)

The Andersons were solid sensible Scottish settlers and were not distracted by vain hopes of gold somewhere beyond the western mountains, but neither were they city folks, and they had no intention of staying in the growing town. Their thoughts were all of farming; they had heard of regions that were opening up far beyond the streets of Sydney. But how to get there? Before they could strike out into the interior they needed a place to live and income to support the growing family.

Sydney sojourn

There was an insatiable need for labour in New South Wales, so prospective employers eagerly awaited the arrival of every new migrant ship. A newspaper article of the time described the arrival of the Alfred:

… the body of immigrants previous to the commencement of the hiring… [was comprised of]… English, Irish, Scotch, and Welsh; while the subdivisions were — principal portion from the West of England, Somerset, the majority of the passengers English; next in ratio Scotch, the Irish were the next numerous ; but the Welsh might be numbered under a score.

The hiring commenced briskly on Saturday morning last, and the demand for servants was good. The following may be taken as the correct average, with rations :

SINGLE MEN.

- Shepherds. £35 to £45 per year.

- General servants. 38 to 45

- Hutkeepers. 30 to 40

- Better class. 40 to 50

SINGLE WOMEN.

- General servants. £18 to £26 per year.

- Laundresses . 26 to 35

MARRIED COUPLES

- Generally useful. £40 to £55 per year.

The best hiring that we heard of, for a family man was, where the immigrant had two boys, one ten and the other twelve years of age; and he succeeded in obtaining £80 a year and rations for all his family—all going to one station in the bush.

Last night, Friday, there were but a few immigrants unhired ; and these consisted of those whose young families were a great barrier to the mothers rendering assistance in this country, where every body has to learn to make themselves useful. Even these families did not number more than four or five—the remaining persons in the depot being those awaiting the arrival of friends to take them to homes already prepared. The number of those who came out by the Alfred through “remittance orders” was large—plainly showing how those already established in New South Wales value the comfortable position in which a labouring family may place themselves by the exercise of economy, temperance, and industry.

(Moreton Bay Courier, Saturday 2 October 1858, page 2)

The Andersons, as has been mentioned above, were immigrants with a “young family,” so were probably seen as less useful than single men and women to landowners looking for workers. There were five children, only the oldest, David, at 14, being of much use as a labourer. Janet, the second child, was 12, so she may have been useful as a housemaid, but the three younger children, William 10, Isobel 8 and James 6, and their mother Ann, who had to care for them, were unproductive as a workforce – more a liability than an asset. It seems unlikely, therefore, that the Andersons were immediately hired by a rural landowner.

It is possible that when they arrived they were met by “friends to take them to homes already prepared,” though the ship’s passenger manifest clearly states that they had no relations in the colony. William Anderson, according to an earlier Scottish census, had been a “woollen weaver” at one stage, even though the arrival documents say he was a farm labourer. Perhaps there was work for him in Sydney in a woollen mill. Somehow he financially supported the family in those first weeks and months. Eldest son David probably also found work, Janet too, though she was only 12. Or else their mother Ann found a job as a housekeeper while Janet was left to care for her younger siblings.

There was no shortage of work in Sydney, especially with the exodus of people to the goldfields. It was surely easy to get a wage in this young colony, but William Anderson wasn’t interested in going back to being a wage earner; he wanted property. As attractive as it must have been William wasn’t tempted by the glitter of gold across the mountains, which he suspected had little chance of lasting success. He wanted to build a completely new life, be lord of his own estate, not be dependant on others. That was the whole reason he had brought his family to this far flung land. So every day he and Ann scoured the papers for opportunities “in the bush,” knowing that eventually something must turn up.

I have found no documentation about the Andersons early months or years in the colony. The first document I have seen attesting to their whereabouts – a death certificate as it happens – is dated some four years after their arrival, placing them not in Sydney but somewhere called “Macleay River,” which as it turns out is some 400 km north of Sydney harbour, and which was then at the very edge of the European settlement of NSW. So at some stage in the years after their arrival, an opportunity had appeared, and they had taken the leap, packing up the whole family and heading into the unknown.

Exactly when they left Sydney I don’t know, but extrapolating back from later events I believe they were certainly there for at least a year. During that Sydney sojourn it would seem that they became acquainted with two other Scottish immigrants, namely the Ross siblings, Helen and Andrew, who arrived in Sydney eight months after the Andersons. The Rosses were from the Highlands, hundreds of miles north of the area near Stirling whence the Andersons had come, so it seems highly unlikely that they knew each other at all before they left on their respective migrations, but the lives of these two families eventually became firmly entwined in the young colony, so they almost certainly met in Sydney.

Helen and Andrew Ross, who were respectively 27 and 23 when they arrived in July 1857, some eight months after the Andersons, faced many of the same questions and challenges, though as two single young adults their situation was somewhat different. Like the Andersons they had no relations in the colony and it was natural that they would gravitate to the Scottish community in Sydney when they first arrived. Fellow Scots were the closest they could come to family. Helen and Andrew I suspect shared many discussions with William and Ann about how to build a life in this new land; their aspirations were similar. None of them saw their futures in Sydney town. They all dreamed of regions beyond, where they could break new ground. (For a possible alternative narrative for the meeting of the Andersons and Rosses, see the notes at the end of this article).

The Macleay Valley

Advertisements for land on a river named the Macleay had started to appear in Sydney newspapers and the unmistakeably Scottish name caught the Andersons’ eyes. Articles like this one in the Sydney Morning Herald (1858) whet their appetite, so that they started making enquiries. Somehow, and at some time, between 1856 and 1860 the Anderson family left the city and moved north. The Rosses would come later, and their final destination would be different. But the Macleay River became an integral part of their story in the years that followed even if it did not become their “forever home” as it did for William and Ann Anderson.

The area the Andersons chose for their future – the Macleay River – had been “opened up” some thirty years previously by wild, rough men (mostly ex-convicts) who sought red cedar, a spectacular tree that grew in abundance in the valleys of Australia’s east coast, the timber of which was in great demand both in Sydney and as far away as Europe. Around 1827 the Scottish commandant at Port Macquarie, Captain AC Innes, had established a government camp for cedar getters at Euroka Creek, on the next big river north of the Hastings, which empties into the sea at Port Macquarie. The big river Innes named the Macleay, in honour of his wife (her maiden name), and the area around Euroka Creek would become the town of Kempsey. Captain Innes would become, over the years that followed, one of NSW’s wealthiest pastoralists, with holdings right up into the New England region over the mountains of the Great Dividing Range.

The “river town” of Kempsey was officially founded in 1836 by Enoch Rudder, a West Country Englishman who acquired land on the southern bank of the Macleay where he grew maize and starting a boat building business. He subdivided his land and was progressively selling off blocks to free settlers who started arriving in the area in the decade after the cedar getters established their camp At Euroka Creek. However, the main part of present day Kempsey was founded on the northern side of the river by another developer. John Verge was a colonial architect who came to the area some years after Rudder, having also been granted land for development by the NSW government. The area that he surveyed and subdivided became the site of the government town in 1854, and is now known as West Kempsey. This was the Kempsey the Andersons would come to know.

John Verge’s land grant extended downstream and one part of it some 10-12 km toward the coast he gave the lyrical name of Austral Eden. The Kempsey library website describes the establishment of this area:

[John] Verge lodged an application … [taking] up a selection on the Macleay, as it was seen as choice down-river country at the junction of Darkwater Creek and the Macleay River, which was thickly timbered with valuable cedar… Austral Eden’s early settlers were immigrants who had rural farming backgrounds. By the end of the 1870s, the location had been transformed into a well-organised rural enterprise of small tenant farmers… Among the early settlers of Austral Eden were siblings George, Peter and Mary Notley, who in 1859 found themselves in Austral Eden after responding to a newspaper advertisement for tenancies. They were typical single immigrants who married in the colony and responded to advertisements offering them a chance to become small landholders.

The article could equally have said “among the early settlers of Australia Eden was the Anderson family,” who came to the area at much the same time as the Notley siblings. Austral Eden was (and is) an area of fertile river flats bounded by a large loop of the Macleay River (see map). It gets a passing mention in a novel about early Kempsey, A River Town, by Australian author Thomas Keneally. The description captures the feeling of the area:

Austral Eden, wide, low, rich land… The river was somewhere near too. You could smell its muddiness, for all the world like the sweet drag of odour you got from a freshly opened two pound can of plum jam. Austral Eden. What a name! Southern heaven.

River journey

There were precious few roads or even tracks outside Sydney in the 1850s especially in the north. The Andersons came to the Macleay by ship rather than overland, sailing up the coast from Sydney past Newcastle and Port Stephens, then Cape Hawke (where the town of Forster later developed), and so to the old penal settlement of Port Macquarie. Access to the hinterland was by big rivers running down from the mountains of the Great Divide to the sea. The Karuah River at Port Stephens, the Coolongolook and Wallamba Rivers at Cape Hawke, the Manning River giving a sea route to Taree and Wingham, the Hastings River at Port Macquarie, all provided access to the forests of the eastern slopes of the Great Dividing Range, where the much sought Red Cedar grew in abundance. North of Port Macquarie one finally came to the mouth of the Macleay, just past the site of present day South West Rocks, a town which did not appear until years later.

Until around 1860, voyages up the Macleay River were usually under sail, as an article from the Sydney Mail (1919) explains (my comments in brackets):

Trade with Sydney in the early days was carried on by sailing vessels, small schooners and ketches. The “enormous freights ruling” [my quotation marks] induced Mr John Verge to invest in a schooner, built on the river and named the Rose of Edin [I wonder if it was really named the the ‘Rose of Eden,’ given the fact that it sailed to Austral Eden as well as other stops on the river]. Steam communication with Sydney was inaugurated by Mr William Marshall, whose first trip in the New Moon in 1858 opened up in a small way a new era in the commercial life of the Macleay…

This paddle steamer New Moon provided the first regular shipping service from Sydney to Kempsey becoming established around 1858 or 59, just when the Andersons were finding their way there. An article from the Macleay Argus (1922) recalls:

“The first regular trading steamer (I think in 1859) was the ‘New Moon’ a small boat of about 30 to 35 tons, which had a profitable trading for several years, till she was unfortunately lost, freights then being very high. She was succeeded by the ‘Fire King’ built on the Nambucca for the same owner, which after a time was also lost. Since then the trade was carried on by steamers of the North Coast Company.” (Mr E.W. Rudder gives the date as 14 November 1857.) The original entrance to the river was at the rocks at the north end of the beach. In 1864 the flood carried a break through at the present entrance. (This entrance is a little north of the South West Rocks.)

Another article, from the Sydney Empire in September 1859, mentions that “the New Moon, steamer, made her usual successful trip, calling at the different farms for cargo in her progress up the river, which she ascended for some miles higher than Kempsey…”

Did the Andersons came by sail, on the Rose of Eden, or by steam, on the New Moon? There is little doubt that they got to know these vessels, and Fire King, well over the years that followed. Whichever boat they came on, they entered the Macleay River at its mouth just south of a headland known as “Grassy Head,” (“at the rocks at the north end of the beach,” as quoted in the above article), followed the river on its passage south, parallel with the beach, until it turned west and inland close to the present day holiday village of South West Rocks. Steaming up the river they entered what was to them a strange and foreign wilderness, a mysterious interior of dense bush and distant mountains. Their new home was beautiful and wild, in some ways not so different (apart from the climate) to the mountains, valleys and rivers of Scotland from which they had come – which the children would mostly forget as they became immersed in their new world – their “southern heaven.”

They disembarked at Darkwater, a small settlement that lay at the junction of the Macleay and another river known as Darkwater Creek, which flows into the Macleay from the south. Both the river and the village were renamed sometime after the Andersons arrived – Darkwater Creek became Belmore River, and Darkwater became Gladstone – the names they bear to this day. Crossing the Darkwater Creek the Andersons came to the wide expanse of river flats that would become their home – Austral Eden – “southern heaven.”

A new home

I have tried to imagine how the Andersons experienced their approach to Darkwater Village. The Macleay Valley is the traditional land of the Dhanggati people, who had lived there for thousands of years, but after the decimation of local Aboriginal communities by white settlers over the previous 30 years, it is likely that the Andersons saw little sign of their presence on that first voyage up the Macleay from the coast, as curious as they night have been.

The myth of an “empty and undeveloped” country waiting to be opened up by industrious British settlers would have been easy and convenient for the Andersons and others like them to incorporate into their consciousness. They did not see themselves as invaders. They did not ask for permission, nor did they offer payment to the local people for the land they acquired. As far as they were concerned they had bought their plot of land from John Verge, a developer, who had been “granted” the land by the Government of NSW. They were probably not very interested in how that government acquired the land from the local inhabitants. Their minds were full of the future, not the past, and how they could survive and thrive in this “untamed land.” The reality of the dispossession and grief of the Dhanggati people was probably far from their minds, though as time went by they surely became increasingly aware that the land on which they were building their lives had not been empty before their arrival, but taken from a proud people who had been pushed to the periphery of society, who had become a mere shadow of their former selves.

The land the Andersons came to at the end of the 1850s was still thickly forested, and timber getters were still felling the valuable red cedar, as well as other trees, for shipment to Sydney and the wider world – in Britain it was sold as “Indian mahogany.” The Anderson family, though they were farmers not timber men, had to clear away much native forest when they arrived. The farm they established once the trees were gone was mixed – crops, pastures, livestock. In the early days maize was the main crop that was grown, and later sugar was planted, with a sugar mill established at Gladstone by CSR, though the occasional loss of sugar cane crops to frosts eventually saw the end of that industry.

Today the river flats of Austral Eden have only small areas of woodland scattered between the fields, and there is no red cedar to be seen. The land is pastoral, lush green fields divided into fenced paddocks. When the sky is grey and overcast, as it was on a day we visited earlier this year, it feels like a bit like the lowlands of Scotland. Cattle graze peacefully on the rich pastures and the mighty Macleay River rolls slow and majestic towards the sea.

Tragedy and change

Records indicate that on 6 July 1860, less than four years after the Andersons arrived in Sydney, their wife and mother Ann (born Ann Hogg) died there, just 46 years old. Was it disease or an accident that took her, or did she die of a broken heart? Perhaps she had never quite adjusted to leaving home in Scotland; perhaps she had never had quite the enthusiasm that her husband had for this new life on the far side of the world and had struggled to embrace this wild and dangerous land. Perhaps the mountains on the western horizon only made her homesick for the Highlands. The migrant experience is often a hard and painful one.

The year she died her children were 18,16, 13, 11 and 9, all of them, I imagine, well able to take care of themselves. Her husband, William, was almost 5 years younger than her, only 42. The year or two since they had first sailed up the Macleay had been hard ones, but with Ann’s help as well as his children and neighbours William had built a home and begun to establish a farm which could keep them alive, on the fertile river flats beside the river. They were pioneers in a beautiful land, but the future must have felt bleak when he laid his wife to rest in the little cemetery in Frederickton, another tiny settlement on the other side of the river between Darkwater and Kempsey.

Ann’s death took a terrible toll on the family. William found himself a widower with five children, two of which were still dependent. David, now a strong and resourceful young man, was his business partner. William, the middle son, at 14 was able to take on increasing amounts of responsibility and the hard labour required on a working farm. Father and two sons worked the land together, while Janet, at 16, become a surrogate mother to her younger siblings, housekeeper for the family, taking care of the challenging practical details of pioneer life, ensuring that there was food on the table and that the younger children, Isobel and James, were clothed and educated. They too had plenty of jobs to do each day to help transform the Anderson property into a going concern.

Starting again

Despite these practical adjustments, their father’s life was lonely, and he was still relatively young with a lot of life before him. There was still so much to do, enough to make it possible to lose himself in his work and suppress the burden of his grief, but his children, especially Janet, who was practical and wise beyond her years, could see he needed a life partner. She knew, of course, that unless her father remarried she would, as the oldest daughter, be forced to accept ongoing responsibilities for him and the farm as he grew older, which would limit her own future prospects. As the first desolate year passed into the second she began to wonder how she could help her father find a new wife, given the hard reality that there was not exactly an abundance of single women in the area.

Her mind may have first settled on Helen Ross, who as far as she knew was still single and working in Sydney. So 18 year old Janet wrote to her with her unusual request, but it was too late: Helen, she discovered, was soon to be married to an English immigrant she had met in Sydney, James Redstone, so “that ship had sailed.”

Janet’s thoughts then went to someone with whom she had kept in contact, a certain Margaret McQueen. Margaret was a lot younger than Janet’s father – at 25 closer, in fact, to Janet’s age than to William’s. Margaret had come out on the same ship as the Andersons back in ‘56. Helen probably knew her too, since Margaret, like Helen, was part of the community of single Scottish women in Sydney. When Helen received Janet’s letter her heart went out to William, and I would not be surprised if the two of them, Helen and Janet, cooked up a plan together to get Margaret hitched to William, despite the nearly twenty year age gap.

Margaret McQueen – I’ll call her Meg for the purpose of my story – was an Edinburgh girl who over the three months she had spent cooped up on the Edward Oliver had got to know the Andersons quite well. William, when he became aware of what was happening behind his back, initially thought Janet’s idea was ridiculous, but he had nothing against young Meg, who he remembered well. William liked the young woman, but he thought of her more as a girl than a woman? Yet such matches were not so rare in the colony, so he gave his blessing to Janet contacting Meg. The letter they received back was more positive than either had expected, so tentatively the farmer and the young woman from Edinburgh began to correspond with each other, with Janet and Helen the matchmakers looking on anxiously.

One thing led to another, the proposal was made and accepted, and in December of 1862 William boarded a boat for the short voyage to Sydney, accompanied by his son David, who would be his “best man” and Janet, who would be a bridesmaid to Meg. The younger children stayed with a neighbor in Austral Eden. On Wednesday 10 December, two and a half years after he had lost his beloved Ann, William Anderson tied the knot again, with Margaret (Meg) McQueen, at St Andrew’s (Scots) Church, at Church Hill, in Sydney. He was 44 and she was 25.

William and Meg married here in 1862

The wedding was attended by old friends from the Andersons first year in Sydney, many of them Scottish immigrants. Helen Ross was there, now Helen Redstone, having married six months previously, in the very same church. Andrew Ross was there too, still single, now 28 years old. He and David Anderson had much to catch up on, Andrew listening intently as David revealed his dreams for the future. Andrew also found his eyes and his thoughts repeatedly drifting to 18 year old Janet, who had grown into an attractive young woman with a compelling personality and a confident smile.

Within days of the wedding the newly married couple as well as David and Janet were back on board the coastal steamer to the Macleay where the rest of the family was eager to greet them. William had gained a wife. His children had gained a step mother. Meg was 25, just 5 years older than David, and 7 years older than Janet, her two oldest “children.” It would be strange if Meg did not feel overwhelmed; it was no small thing she had taken on. But this was the same woman who had resolved to sail around the world at 19 to start a new life in a land where she knew no-one, a land from which she knew she would probably never return. Meg McQueen, now Meg Anderson, was no ordinary woman, and she was determined to make the best of it. The marriage was a successful one. They had six children and were together over fifty years before William died in 1916.

William became a successful farmer on the Macleay River and his big family were well known in the area. Anderson remains a common name on the mid north coast of NSW to this day, among both the white and the indigenous communities. There were presumably other Andersons who came to the area, and families in those days were big. There was, to be sure, mixing between the indigenous and British peoples, but at times Aboriginal people, who had no surnames in their language, simply took on the name of British settlers for whom they worked, or with whom they had other connections.

My own ancestors were not Andersons but Rosses. The Ross siblings Helen and Andrew had got to know the Andersons, I believe, in Sydney, and became re-acquainted in 1862 when William married Meg at Scots Church. The connection might have ended there but for Andrew, who through that conversation with David at the wedding had caught a vision for the distant mountains and valleys of NSW’s Mid North Coast; it seems he had also caught a vision of the delightful Janet who, even after the Andersons had departed for the Macleay, he could not get out of his mind.

Notes:

- The story above is largely from my imagination. I have only a few facts on which to build. If any descendant of the Anderson family reads this and see errors, please let me know by adding a comment to this blog.

- I have no document that attests to the meeting of the Andersons and Rosses in Sydney, but have extrapolated backwards from the facts of their subsequent connections, which will be explored in another article

- I do not know when the Andersons came to Austral Eden, but the death of Ann on the Macleay in 1860 is documented.

- An alternative narrative for the meeting of the Rosses and the Andersons is that they did not meet in Sydney at all, but that the Andersons departure for the Macleay actually happened soon after their arrival, and that William had returned to Sydney when the Alfred docked, hoping to recruit workers for his holding in the Macleay Valley. It may have been that Andrew, a newly arrived strapping young Highlander fitted the bill and travelled north with William to join him on the newly opened up land. Helen, on the other hand, stayed in Sydney, where work for a single woman was easier to find. If so, it would mean that Andrew Ross was living up country from soon after his arrival in Australia, and became in effect a part of the Anderson’s enterprise.

- The circumstances of William’s remarriage are uncertain, but the date and place are documented.

- William second wife was named Margaret McQueen, and she was from Edinburgh. The shortened name Meg is guesswork on my part.

- William died in 1915 when he was 97 years old. Margaret died 17 years later in 1932 at age 96. Both are buried in Kempsey

- A River Town, by Thomas Keneally, is a novel about Kempsey and the Macleay set at the turn of the century – 1900 – some 40 years after the Andersons settled in Austral Eden. It paints a vivid picture of an Australian country town at that time.

Thank you as always for your Forgotten Tales …and have a happy Christmas and eventful New Year .

Wendy Williamson

Upwey Victoria 🙂

You too Wendy! Merry Christmas!

Dear David,

Firstly, the joys of the season to you and yours. Please read that sentence again with an Irish accident.

Your Anderson research and the relaying of it is amazing and a most enjoyable read. I am about to read it again as it arrived during a very busy time at my place and my initial cursory reading didn’t do it justice. Preparing for a new kitchen! Yay! It is amazing how much “stuff” one can accumulate in 20 years in a kitchen. Much of that “stuff” is now in boxes in my dining room where every flat surface is covered with those boxes and access is limited. What a mess.

In the middle of all this turmoil my son asked me if I could have his dad for about a month as they both needed a break. Worked well as George had an appointment with his geriatrician down here (your vintage – Simon Chalkley). Simon found that there had been some further decline in George’s cognitive skills, but commented on how well he appeared physically. Sadly just a week later I woke to hear George coughing and went to his room to check on him. He nodded a positive response and I went to shower and dress thinking that he looked very tired. When I returned his position in bed and his breathing had altered and he did not respond to me. Ambulance called and they talked me through CPR until the paramedics arrived. Neither my efforts nor theirs were able to save or resuscitate him. We are terribly sad, but console ourselves that he died suddenly, though peacefully. He still remembered his old mates, was able to dress and feed himself, still understood comedy and on a good day could come up with an accurate diagnosis given a set of symptoms. George 1 v Alzheimer’s 0.

It has been a rough couple of years for David and for me and I worry constantly about him. He has not recovered from his brother’s death, less than two years ago, and is missing both has brother and his dad immensely. Although George and I divorced we retained regard and respect for each other and it is a strange world without him in it. I am now prompted to get all that I know of his family down on paper. George was born in Poland only days before the Nazis invaded and his parents fled across the boarder with their tiny baby, his 12 year old sister and 8 year old cousin. By the time they got into Russia, Poland had capitulated and they then became prisoners of war instead I’d refugees. The first six years of his life were spent in a prisoner of war camp.

No family history has been pursued for a while so I think your Anderson and Ross research has whetted my appetite once again. As I have mentioned the “other side” of my mum’s family has Andersons, including an Ann – my great grandmother. There is also a link to Ross, but it is complex and confusing. My grandmother Jessie (Lawrence) Byrne wrote to a Finlay Ross, from Forfar from memory, for many years.

Oh gosh, I’ve done it again ….. another long note that won’t cure the world’s ills.

Best wishes for the New Year.

Barb.

Sent from my iPad

Hi Barb and a Happy New Year to you too. I was sad to hear your news, you and David have really had so much to cope with these last few years. I am so glad you have resolved to get George’s story down on paper. Please let me read it as it unfolds. His family’s journey sounds like an extraordinary one. I really feel for your David. So much loss, and so much tragedy. Maybe we will meet up some day. I have some more information about the Byrne family… but as you can see I am up to my eyeballs in Andersons and Rosses at the moment, so it has been put aside until later. Please drop in next time you are heading up to the Valley.