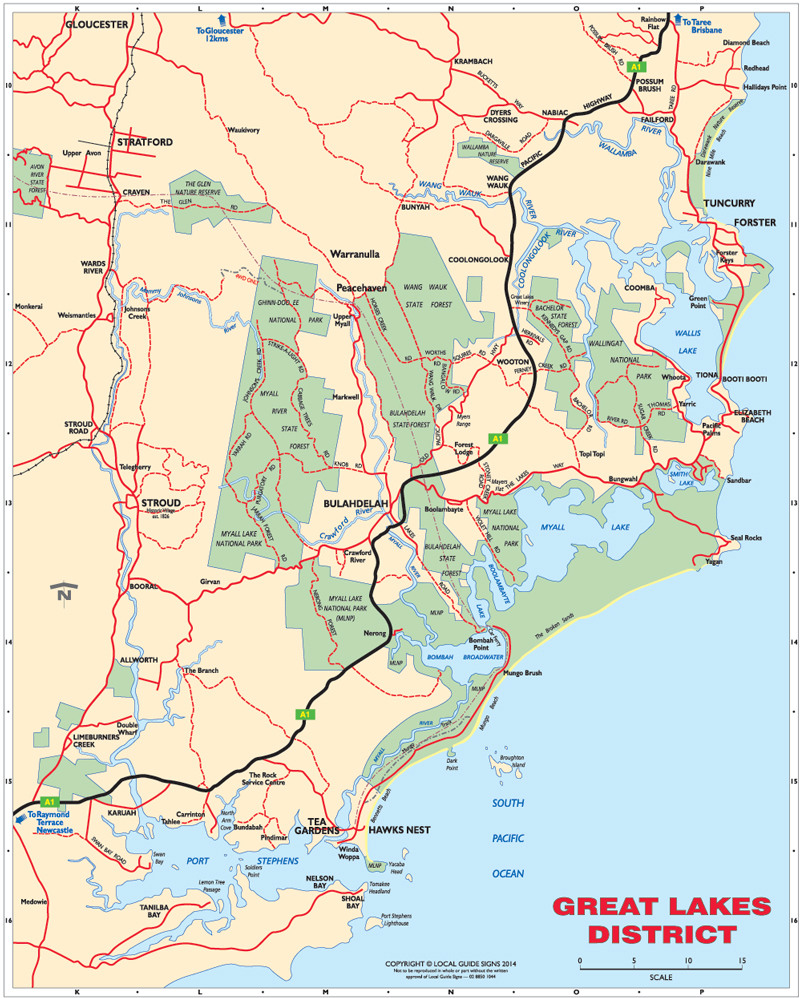

Driving north from Newcastle on the Pacific Highway, the main route from Sydney to Brisbane, one passes Port Stephens, the huge and beautiful harbour which was once slated as a possible national capitol for Australia, before entering the so called Great Lakes District of the Barrington Coast of NSW. Stretching from Port Stephens to Forster and Tuncurry , the lakes encompassed by the region include the enormous Myall Lakes system, the smaller Smith Lake, and Wallis Lake. They are saltwater lakes, expansive estuaries, separated from the sea by long strips of land that vary from a few hundred metres wide to nearly 10km. West of the lakes, forest and rolling green hills rise gradually to the rugged heights of the Great Dividing Range. The northward highway, between the mountains and the sea, crosses one ridge after another: the eucalypt forests are verdant and dark, with scatterings of skeletal bushfire ravaged gums stretching their ghostly fingers above the canopy.

Biripi Country

The Worimi and Biripi peoples have inhabited these lands for many thousands of years (the Worimi Nation stretches from the Hunter River to the Wallamba River, the Biripi [Birpai] Nation from the Wallamba to the Hastings), but the European incursion began only a little over 150 years ago. Forster, a coastal town lying at the foot of the headland which was named Cape Hawke by James Cook, was the earliest British settlement on this part of the coast. Halfway between the convict settlements of Newcastle and Port Macquarie, it was a commercial hub for smaller settlements which began to spring up further inland. In those early days there were no roads in the area and travel was by coastal steamer, or sailing ships. The Aboriginal peoples, of course, had routes through the bush which they had used for centuries, and could travel quickly across wide expanses of country, but the same land looked to the European newcomers like an impenetrable wilderness. An account of that time which I read recently described the journey from Port Stephens to Nabiac (west of Forster) as a ten day trek through the bush, mostly sleeping rough, though there were scattered homesteads which offered some refuge to hardy travellers. Nowadays the same journey by road takes less than an hour.

The rivers of the hinterland

Many of the big rivers that begin in the mountains, tumbling down to the coastal lakes and the sea, are navigable for vessels for many miles upstream from the coast. Wallis Lake lies at the end of the Coolongolook River, which empties into the sea between Forster and Tuncurry. The Wang Wauk River merges with the Coolongolook before it becomes Wallis Lake. The Wallamba River empties into the northern reaches of Wallis Lake, thereby also losing itself in the Coolongolook.

In the old days, these rivers were the main route to the interior for European settlers. Crafts of various types plied their waters; going upstream with the incoming tide and coming back down when the tide turned, they brought stores to the tiny settlements further inland, returning with loads of timber and other produce.

The earliest (European) industry in this Mid-North Coast area was timber cutting. The famed red cedar was ideal for building anything from furniture to ships, with trees growing along the river banks and back into the hills. Itinerant timber men had been stripping out the highly prized red cedar since the 1830s, long before farmers started settling the area. Once most of the cedar had been removed, the timber industry turned its attention to native hardwoods that grew in abundance on the hinterland, readily accessible from the river. The demand for timber was insatiable in Sydney where building had been going on apace since British settlement in 1788, and saw-mills started to appear all over the Mid-North Coast, from Port Stephens to Coffs Harbour and beyond.

The Breckenridge family comes to Forster

Wikipedia mentions that the first Post Office in Forster opened in 1872 with a certain John Wylie Breckenridge (1818-1899) as its postmaster, on a salary of £10 per year. John Breckenridge with his wife and two eldest children had migrated from Scotland in the 1860s, and moved to Forster to become involved in the burgeoning timber industry. As was so often the case, one sibling after another followed John from Scotland – he was one of 13 although they didn’t all migrate. Many of the Breckenridge family settled on the NSW coast from Newcastle on the Hunter River northwards to Port Macquarie on the Hastings. Some became involved in the timber industry, others were merchants of various sorts. The Breckenridge family also built ships which operated on the rivers and coast of NSW. John’s oldest son and namesake became one of Forster’s leading citizens, establishing sawmills in Nabiac and Failford on the Wallamba River and later further north at Kendall on the Camden Haven River. He was also involved in ship building on the river. The village of Failford, established around the timber activities, was named for the village south of Glasgow in Scotland which had been the Breckenridge home – where both John Breckenridges – senior and junior – were born. For more Breckenridge history see this website, which features a picture of ships tied up at the Failford wharf.

Hugh Breckenridge (b.1845), a much younger brother of the senior John (b.1818), did not leave Scotland till many years after his brother, arriving in early 1875. On the ship on which he sailed from Britain he met a lovely young Irish woman who was also journeying to Australia – Kate Hickson, originally from Co Kerry. Shortly after they arrived in Sydney they married, and moved to Forster, where Hugh established a bakery. He later had a stores boat which sailed up and down the Wallamba River between Forster and Nabiac to deliver supplies of various kinds.

Kate Hickson’s sadness

By the time she married Kate had been in Australia for 12 years, and she had grown from shy child to adulthood. She had first migrated in 1863 when she was 18, traveling with her brother George, who was a year younger. They had been sponsored by an older sister of theirs who had come to Australia earlier. In fact three of Kate’s older sisters had migrated before she and George came over. The first to come, Susan, had left Ireland in 1853, the year their mother died. Mary and Ellen came in 1857, followed by George and Kate in 1863.

However, unlike her older sisters Kate did not immediately find someone to marry, and I imagine those first years in Australia she and her brother George remained very close as they came to grips with this strange new world. I presume they shared a house, or perhaps lodged with family or other contacts. After George married Agnes Harper in 1870, Kate remained closely connected to her brother and his new wife. None of them was prepared for the tragedy that struck a few years later. In December 1872, George and Agnes’ first born, Richard, died when he was only one day old. A year later their second child, Lily, died at three weeks. Then, barely six months later, George himself also died, aged just 28. I have no idea what he died of but I have wondered if it was just that his heart was broken. Agnes would have been desolate, and Kate, auntie to the two infants, must have been distraught.

Grief stricken, she boarded a ship and made the long sea journey back to the old country, though her purpose in doing so I have not managed to discover. Perhaps, like many of us when we come to the end of ourselves, she just did not know what else to do, and thought perhaps she would find some purpose or meaning in her native land. But Ireland had changed, and England had never been her home. All of her immediate family had left Kerry – she herself had been gone 11 years, long enough to feel she no longer belonged in the land of her birth. She met old friends, but realised quickly that her home now was Australia, and there was no longer a place for her in the Kerry of the 1870s. So after a short sojourn in the northern hemisphere she joined another ship and found herself again at sea, heading back to Sydney. It was on that 3 month voyage that she met Hugh Breckenridge, who would become her husband.

Hugh and Kate Breckenridge

It’s hard to imagine what Kate, not to mention her Scottish husband, would have made of Forster in 1876 when she and Hugh moved there. Forster is today a town of around 15,000 but when Kate and Hugh came to join his older brother there cannot have been more than a few hundred in the settlement. It was accessible only by sea; there were no roads in those days. Kate must have felt she had come to the end of the earth as their ship sailed through the channel between the spits of Tuncurry and Forster.

The town, initially known as Minimbah, had only been surveyed in 1869, 6 years before Hugh and Kate arrived. In 1870 it was renamed Forster. Hugh had grown up close to the west coast of Scotland, Kate near the west coast of Ireland. Since childhood they had known the beautiful beaches of their native lands, on the edge of the Atlantic, so often wild and grey. Now they found themselves on the east coast of a huge, wild continent, where the skies were almost always brilliant blue, and the sea glittered in the piercing sunlight. This was the home of a people whose language and ways were strange to them, an ancient people who had been walking these beaches and fishing these waters for thousands of years, the Biripi people. It was in this strange and distant land on the edge of the mighty Pacific Ocean that Hugh and Kate made their home.

I would like to think that their relationship with the First Nations people, the Biripi, was good, and that the Breckenridge children grew up playing with Aboriginal friends, swimming in the rivers and sea together, fishing in the lake, hunting kangaroo together in the bush, learning the customs and language of the people on whose land they were living; if only it had been like that, for the Breckenridge family and for every other newly arrived family from Britain. If only the first 200 years had been the way they should have been, how much better a land we would have lived in now. But I know that such thoughts are wishful thinking, that the reality was far from this idyllic picture, and that the children of white settlers like the Breckenridge family probably had little if any contact with Biripi people, whose numbers had been decimated by dispossession, disease and death resulting from the unwelcome British invasion of their ancestral lands (for a brief overview of Biripi history see here).

Over the next ten years Hugh and Kate had six children. The first, a daughter, May, was born in North Sydney in 1877, but the next four were born on the Mid North Coast, registered in Port Stephens, Forster and Wingham. Their last daughter, named Kate after her mother, was born in 1886 in Sydney, but died in infancy. Exactly when Kate and Hugh moved back to Sydney for good is uncertain, but Hugh’s bakery continued to be a registered business in Forster until the 1900s.

John Hickson in Nabiac

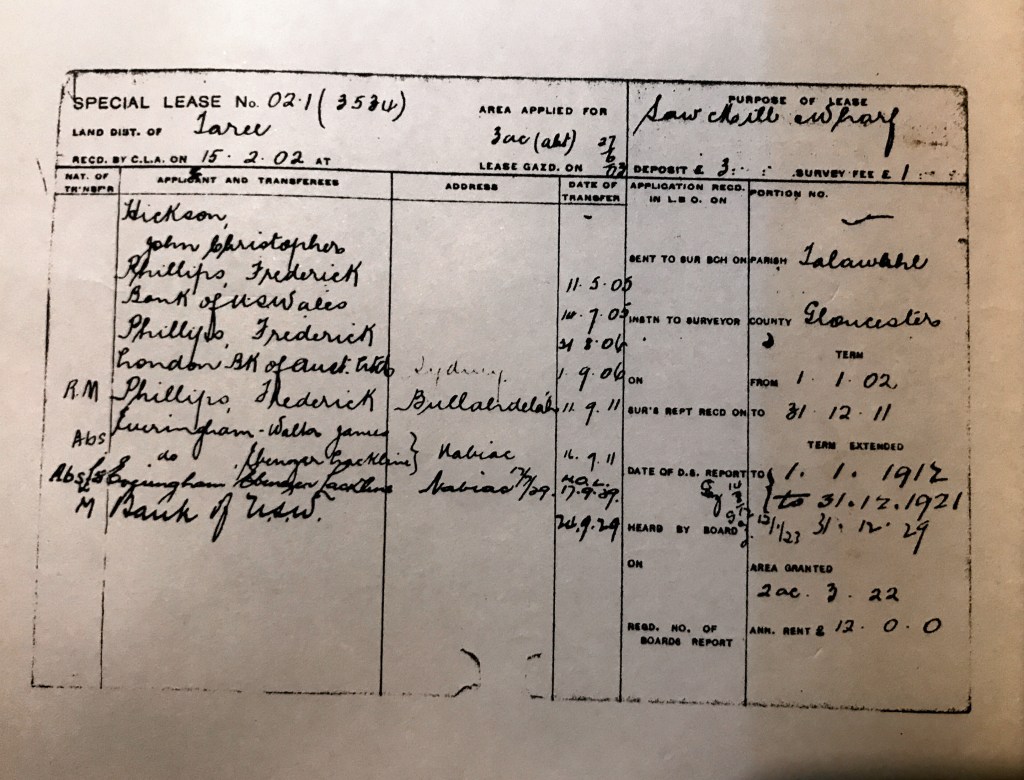

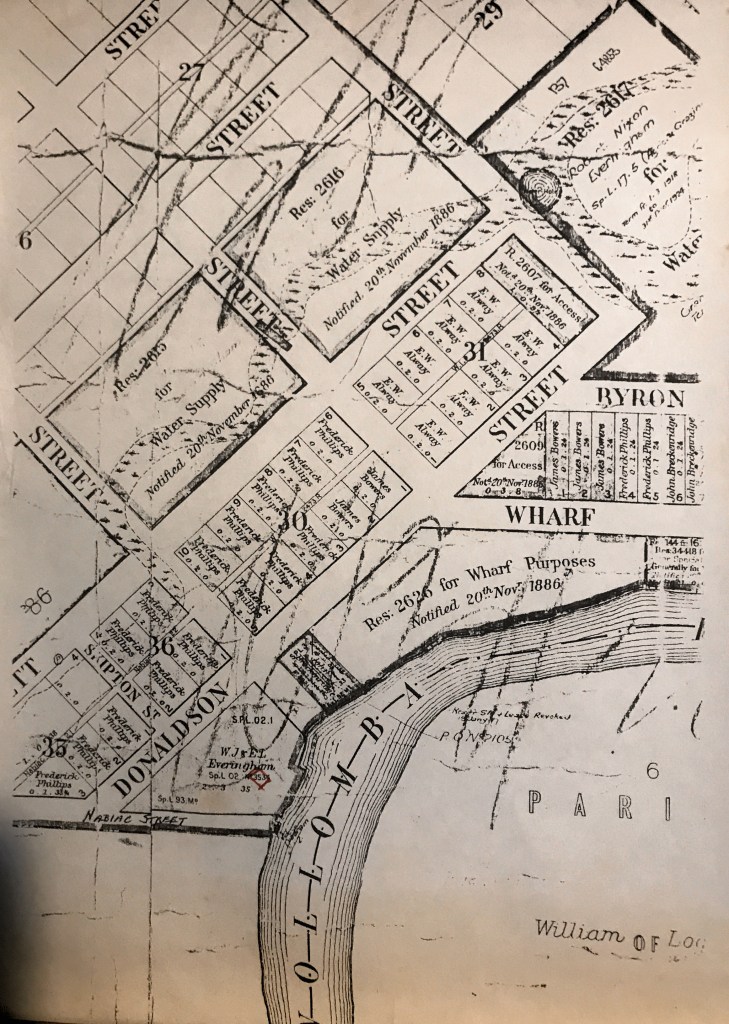

Kate’s youngest brother was John Christopher Hickson (JCH), born in 1848 in Killorglin, Kerry. He had come out to Australia four or five years after Kate, around the age of 20, somewhere between 1866 and 1870, the last of the Hickson children to leave Ireland. He found work with a timber merchant in Sydney, George Hudson, but soon branched out on his own, setting up a timber yard initially in Darling Harbour, later moving further up the Parramatta River to Burwood, near Enfield where he lived. Through the contacts afforded by his sister Kate’s marriage into the Breckenridge family, he soon began to source his timber from the Mid-North Coast, no doubt transporting lumber to Sydney from John Breckenridge’s sawmills in Failford on the Wallamba, and Kendall on the Camden Haven River. Eventually John Hickson established his own sawmill and wharf in Nabiac, together with a business partner from Bulahdelah, but he never lived in the area. I have a copy of an application made by John in 1902 for a lease of land on the Wallamba River, for a wharf and timber mill, but I am fairly sure he had been there long before that year.

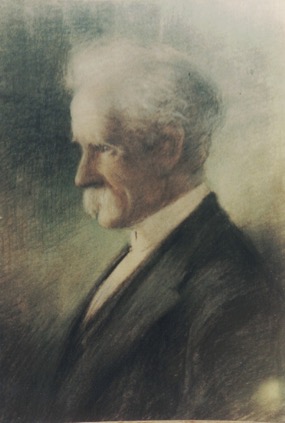

John Hickson made his fortune through timber from the Great Lakes district of the Mid North Coast. His older sister Kate and her husband were never as wealthy as he, but they seem to have had a comfortable life. I wonder why they chose to move back to Sydney. Perhaps Kate just felt too isolated from her wider family, perhaps she missed Sydney society. Perhaps it was Hugh who was not cut out for a life in the remoteness of the Australian bush at the end of the nineteenth century. According to Don Robinson he was an artist of some achievement, and perhaps city life was more stimulating for him.

Working in Taree

As fate would have it, I started a new job in Taree last month (July 2022), working for the Biripi Aboriginal Medical Service in that town. I knew little of the history I have just related when I started there, though I knew that John Hickson had connections with Nabiac. Taree lies some 35km north of Nabiac on the mighty Manning River, and is nowadays the biggest centre of population between Newcastle and Port Macquarie. I stay over in Port Macquarie three nights a week in my parents’ holiday flat, driving to Taree every morning. As I drive over the Camden Haven River at Rossglen I think of John Breckenridge junior and his mill at Kendall, a quaint little village just west of the Pacific Highway.

On Thursday evenings after work I drive southward, home to Lake Macquarie. The highway passes Failford and crosses the Wallamba River at Nabiac. I usually stop for petrol at Coolongolook, before continuing south toward Port Stephens. As I cross this district, the Great Lakes, the Barrington Coast, I always find myself thinking of my ancestor John Hickson, the wealthy timber merchant of Sydney, his sister Kate who married into the Breckenridge family of Forster, and the tragedy of their brother George’s passing so young, after the deaths of his two infant children.

And seeing as I work now for the traditional owners of the land on which these Irish and Scottish settlers made their lives so far from their native land all those years ago, I also ponder much on the Biripi people, wondering about their thousands of years history, and whether the wrongs of the past inflicted on them by those early white settlers and a government that saw them only as a dying race can ever be compensated, so that the abused and dispossessed First Nations descendants might find it in their hearts to forgive this awful legacy. We need a vision of the future which sees us all as one, the dividing walls of race and history demolished, a future where we can all celebrate the good things in our respective histories and cultures, and draw from both the things on which we can build a new Australian identity where friendship rather than enmity is the spirit that marks us as a nation.

Wow you always provide such interesting articles, thank you. My brother so your (???th) cousins however many times removed moved from Sydney to Minimbah a few years ago next time we travel to Sydney I’d love to catch up for a coffee and chat. Take care Jennifer

Sure, lets have coffee sometime!

Loved this Forgotten Tale. Always interested in the Hicksons even though my connection is tenuous, Kerry burns deep in our shared genes.