Back in the middle of the nineteenth century a family named Hickson lived in Killorglin, Co Kerry, Ireland. Husband and wife were Richard and Mary-Ann; they married around 1830 when he was 23 and she 18, though I have not been able to find exact dates for their respective births. They had seven children who survived to adulthood, though there were, according to the writings of their youngest son, more children who died in childhood, though he never recorded their names.

Richard was a nailor, a trade forgotten now, but at the time quite common. Nails were made by hand out of iron in a forge, meaning that nailors were basically blacksmiths, and spent their days hammering over a glowing bed of coals. A hard profession, no doubt, but the strenuous physical work over a furnace would at least have kept them warm, in a country renowned for its cold wet days. At least two of Richard’s sons became nailors, according to various documents that I have uncovered, though neither of them continued in the trade. Even Richard himself may have left the heavy work behind at some stage, since many years later, on the death certificate of one of his sons, Richard’s profession is recorded as “shopkeeper.” But what shop would he have kept in Killorglin in the 1850s and 60s?

Mary was wife and mother. Her last name was Carter, betraying English heritage, like her husband. I have not found much information about the Carter family of Kerry, but at least one other turns up in my family’s Kerry story of those years. A certain Susan Carter, who was a few years younger than Mary-Anne – and was probably related – married George Needham of Templenoe, a village south of Killorglin on the other side of the Iveragh Peninsula. George and Susan’s first daughter, Mary Needham, would later marry Richard and Mary-Anne’s first son, William Hickson.

Anglo-Irish

There were many Hicksons in Co Kerry in those days, all with a common ancestor, Christopher Hickson, who had come across from England in the late 1500s during the so called Munster Plantation. By the nineteenth century the Hicksons had been in Ireland for over two centuries, and they thought of themselves as thoroughly Irish, just as we “white” inhabitants of Australia, after 250 years of “British occupation,” think of ourselves as thoroughly Australian. However, the Hicksons and Carters were part of a social grouping in Ireland which was often known as the “Anglo-Irish,” a group which was separate in many ways from the “native Irish” who could trace their ancestry on the island back for millennia rather than centuries. These people had a sort of dual identity, Irish yet also proudly British. The native Irish, however, often saw the Anglo-Irish as representative of the “evil Empire” – the British, and would have been happy for them to go away and leave them in peace.

The Anglo-Irish struggled sometimes with their identity. The Wikipedia article on this subject cites, for example, anAnglo-Irish novelist and short story writer Elizabeth Bowen, who “described her experience as feeling ‘English in Ireland, Irish in England,’ and not accepted fully as belonging to either.” (Quoting from Paul Poplowski, “Elizabeth Bowen (1899–1973),”Encyclopedia of Literary Modernism)) I suspect that our Hickson forebears may have experienced something of this same confusion, just as many of us feel even now, in our contemporary world in which nations have been so jumbled together over the last 300 years of migration, and in which frequent and easy international travel, work and life that so many of us experience today leaves us wondering sometimes, who are we really, and where do we really belong?

The idea of Anglo-Irish was and is, in the minds of many, linked with the aristocracy of Ireland before independence in 1921. However, though there were certainly some descendants of Christopher Hickson in the nineteenth century who were “aristocracy” – landed gentry, military men and clergymen – others, probably the majority, were “commoners,” and our Hickson forebears were some of these. But they were all Anglo-Irish at a time when anti-British sentiment was growing in Ireland. They were also all Protestants in a majority Catholic county (most, though not all, Anglo-Irish were Protestants, members of the Church of Ireland). Though they surely had many friends among the native Irish, both Catholic and Protestant, it must have been increasingly hard to be part of a minority group (even at its peak the Protestant population of Co Kerry was never more than 10%) that was not really wanted. Though they were not desperately poor like so many of the tenant farmers of County Kerry, and though they weathered the ravages of the Irish famine better than others, they too must have seen the new worlds of America and Australia as lands of opportunity which Ireland could never offer.

So for the Hicksons the “pushing factors” in their migration were about feelings of rejection and the desire for religious freedom, while the “pulling factors” were more about better opportunities. I suspect that these were the reasons that all my Hickson family left Ireland in the 1850s and 60s. They did not, however, all leave at the same time.

Their mother’s passing; emigration begins

The exodus started in 1853, apparently triggered by the tragic passing of their beloved wife and mother, Mary-Anne, when she was only 41 years old, leaving Richard a widower with seven children. Mary-Anne lies buried in the Killorglin graveyard, along with some of her unnamed children. That same year, the oldest of the Hickson family children, Susanna, migrated to Australia. A few years later (1855) she was followed by her younger sisters Mary and Ellen.

There were, in a sense, two groups of Hickson children, those born up to 1840 and those born after 1840. Susanna was first born (1831), closely followed by William (1832). Mary and Ellen were born in 1835 and 1840 respectively). I suspect that there was at least one other son born in the 1830s, who would have been named Richard, like his father, since that seems to be the way the Irish of the time named their children, the second born son receiving his father’s name, and the second born daughter her mother’s. The second group of children were Catherine (Kate, born 1845), George (1846) and John (1848). The three older girls all migrated in the 1850s, the three youngest children Kate, George and John, in the 1860s.

The family attended St James (built 1809), the Church of Ireland in Killorglin, a building which stands to this day, though it is no longer used as a church. The children went to the Protestant school, near the Killorglin cemetery, looking out over the green hills of Kerry. From what the nostalgic John wrote in later days, it was a happy childhood. John had a flair for writing in verse; the following comes from his 1893 book Notes of Travel:

Now I muse of days of childhood, which have passed by long ago,

When as children we were happy, and life’s crosses did not know;

When no care or trouble rested on our hearts so light and gay,

When we thought of nothing better than of pleasure all the day.

When to school we with our brothers o’er the bridge we’d briskly walk,

Some new play or sport or pleasure, was the subject of our talk:

With our books in strap or satchel, on our shoulders loosely swung,

Then ere school commenced its duties, some nice hymn was sweetly sung.

Ah! the dear old thatch-roofed schoolhouse, with its turf fire and clay floor,

And its plain deal desks and benches, and the wainscot near the door… etc

Last year I had an email from Stephen Thompson, secretary of the Killorglin Archives Society. He commented on the location of the schoolhouse which the Hickson children presumably attended, which is no longer there. He told me that the old Protestant schoolhouse “was directly opposite the entrance to Dromavally graveyard. Some years ago, a group of Tidy Towns volunteers cleared the ivy from the entrance doorway to the school premises – photo attached.” My daughter Hanna and I visited the graveyard in 2016 when we were in Killorglin, but it never occurred to me that the school that the Hickson children had attended had been right across the road.

For the few years after their sisters had all left (1855) and before William married (1858), Kate was the “mother” of the family, the only female left with three brothers and their father. She had been just 8 when their mother died and 10 when Mary and Ellen left for Australia. She was presumably still at school with her younger brothers George and John, but with father Richard and William out working every day, she and her brothers would have had many responsibilities in the family home.

Living in Sneem

At some stage (between 1855 and 1858) the family seem to have lived in Sneem, on the other side of the Iveragh peninsula from Killorglin, a half day’s journey from Killorglin either around the coast or over the mountains on gravel roads that were a challenge in wet weather. Transport in those days was by horse, or cart (jaunting car), or by foot, and the weather could be wild along the Atlantic coast of Kerry.

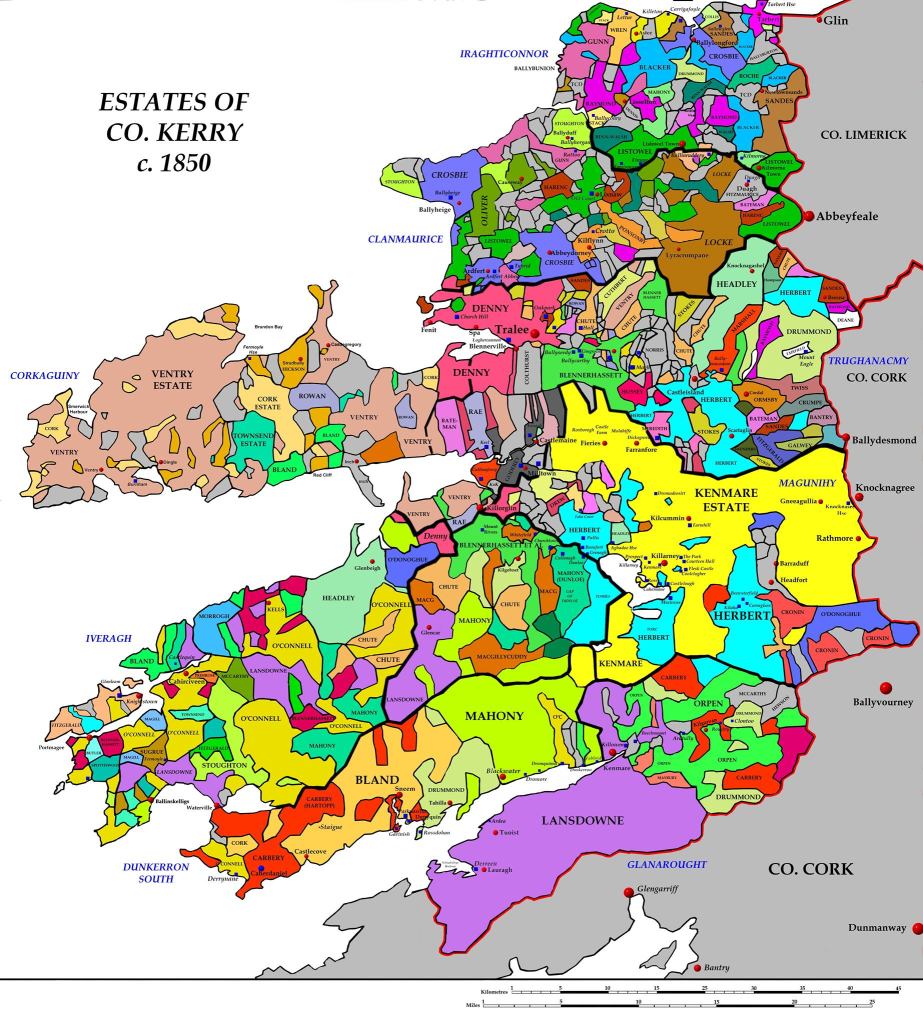

The fact that they lived in Sneem and attended the Sneem Church of Ireland is recorded in young John’s book, but he does not mention why they moved from Killorglin nor how long they were away. Perhaps they spent three whole years in Sneem after Mary and Ellen left in 1855, and I have previously postulated that their reason for moving was so Richard and his son William could work as nailors on the Derryquin Estate, which was owned by the Bland family. The Hicksons, as mentioned before, had family connections among the landed gentry of Kerry, and they would have been known to the Blands, and the Mahonys, who were the two major families with estates on the Kenmare River estuary (see map of estates). The Mahonys were well known to the Needhams, since the Dromore Castle where they lived was very close to Templenoe, where George Needham was a parish clerk. I imagine it was during that time in Sneem that William’s friendship with Mary Needham blossomed. They married in Templenoe in 1858, and I suspect that all the Hicksons moved back to Killorglin some time after that.

Back in Killorglin 1858-1865

By 1858 Richard was 51 and no doubt heavy blacksmithing work was getting harder for him. But he still had to provide for his family, at least the three younger children. It is possible that he found other work during this time – his son John, many years later, recorded on his brother’s death certificate that their father’s profession was “shopkeeper.” I have no further details than that – what shop he worked in I don’t know, and whether he was a shop owner, or just a shop keeper is equally unclear. I do know that one of young John’s best friends at school was Roger Martin, who later operated a hardware and general store in Killorglin. The Martins seem to have been family friends of the Hicksons. I suppose it is possible that Roger’s father may have owned a store in Killorglin in the 1850s where Richard found employment. Whether that was the same store that Roger later owned I do not know. Roger Martin’s Store was in Langford Street, and remains to this day, under different ownership.

Kate, just 12 when they moved back to Killorglin, and possibly still at school, was busy with running the household. She was thankful for the addition of Mary, William’s new wife, to the family, and an older sister (in law) for her. William and Mary likely lived with the rest of the family in Killorglin. Over the next five years three children were added to the Hickson household in Killorglin, born to William and Mary in 1859 (Richard), 1861 (Susan) and 1863 (Sarah). These were the last of our Hickson ancestors to be born in Ireland. The years between 1858 and 1863 must have been busy and happy ones, a new generation bringing meaning and joy to the family after the sadness of death (mother Mary-Anne) and the separation of emigration (the three older sisters).

The family economy in those years was probably bolstered by William, presumably still working as a blacksmith or nailor, though he had a family of his own to support. George, when he finished school, followed his older brother’s lead, becoming an apprentice nailor when he turned 15 in 1861. John, the youngest, probably finished his schooling around 1863, but in a departure from family tradition started an apprenticeship as a merchant, perhaps in the same business as his father.

Another upheaval rocked the family in 1863, when Kate and George, by then respectively 19 and 18 years of age, decided to make the move to Australia, following their older sisters who by then were becoming well established in Sydney. Susan and Mary were both married with children, and Ellen was “in service,” house servant to a Dr Bellamy in the growing city. She too would marry in 1865, about 17 months after the arrival of Kate and George. The remaining family in Killorglin consisted of Richard, the patriarch, oldest son William with his wife Mary and three little children, and John.

Much was happening in Kerry in the 50s and 60s. There was growing agitation for independence from Britain, of which I have written elsewhere. Paradoxically, the visit of Queen Victoria to Killarney in 1861 was greeted by the general populace, and especially by the minority Anglo-Irish community, with great excitement, with thousands lining the streets to greet her. Despite the rise of republicanism in Ireland, royal fever gripped the community, and the Queen was applauded by thousands lining the streets. The Queen was overwhelmed by the beauty of the Kerry landscape, which has been a well known tourist destination ever since. Tourism was an infant industry in the Victorian age, only open to the very rich. Now, of course, it is a part of many of our lives, and Killarney has benefited massively from the obsession with travel that now grips the Western world. Killarney today is filled with hotels and activities, the quintessential Irish destination, with the so called Ring of Kerry (which goes through Killarney, Killorglin, Sneem and Templenoe), and the spectacular Dingle peninsula, some of Ireland’s most popular tourist routes.

Also in 1861 there was a religious revival in the Church of Ireland, centred on Templenoe, but spreading throughout the county. This resulted in the formation of a new branch of Christianity, which eventually became known as Plymouth Brethren. Templenoe was, of course, the hometown of William’s wife Mary, and her family (the Needhams) was caught up in this revival. William and Mary, it seems, were also deeply affected, as were many of their closest friends, including a certain George Byrne, another nailor, and his wife Sarah (Ruddle), who lived in Killarney. George’s son would later marry William’s daughter, Susan, and they remained staunch Brethren till the end of their days. One of their five daughters was my grandmother. I have told their stories in other articles here, here, here, here, here, and here.

The Needham’s decide for America

Perhaps it was this revival that became the catalyst for the Needham family leaving Ireland. As well as that, in 1863, two years into the Kerry Revival and the same year that Mary and Ellen left for Australia, the older Needham, George, died. His wife, Susan (Carter) had died in 1856 just a few years after her relative, Mary-Ann died. George remarried in 1862, but died later the same year, at the age of 60. This must have been a terrible blow for his ten children, the youngest of whom was only 6 years old. Over the ensuing years all of the Needham children would leave Ireland. Not only were they not Catholic, but now they were no longer Church of Ireland, and many in Kerry saw the Plymouth Brethren as an extremist sect, even if the brethren themselves were only committed to living what they understood to be authentic Biblical Christianity. The Needhams, with many of the other non-artistocratic brethren longed for a new world where they could pursue their faith without criticism. Interestingly, though many of the landed gentry in Ireland were equally affected by the Brethren revival but unlike their poorer brethren they had no economic motivation to leave Ireland, living a life of wealth and privilege. The Needhams saw the greatest opportunity for religious liberty in America (aware no doubt of the ascendancy of the Church of England in Australia), and all of them eventually ended up in Massachusetts, around Boston, though their descendants are spread widely through the USA and Canada.

William and Mary, unlike all the Hicksons to date, decided to go with the Needhams to America. They took William’s father Richard with them, as well, of course, as their three children. The Hickson family home in Killorglin was sold, assuming they owned a home, though this is something I have been amiable to verify. It was an expensive venture, to move and re-establish on the other side of the Atlantic. The story of the Hickson’s in America will be the subject of another essay.

The last of the Killorglin Hicksons leaves Ireland

But even then the Killorglin Hicksons still had one representative in Ireland, namely young John, who was 17 when his father and brother left. He may have found lodging with the Martin family, no doubt keen to stay in Ireland to complete his training before heading into the wide world. It is not clear exactly when he did leave. If he had started a five year apprenticeship in 1863 he would have finished in 1868, but the may have been bonded to his “master” for a few years after he was “qualified.” In any case, although some records suggest that he may have arrived in Australia as early as 1868, the only definite record of a John Hickson in a passenger arrival list is in 1870, when he is recorded as disembarking from the Caduceus, in Melbourne. His older sister, Ellen, had moved to Ballarat shortly after her marriage, and he may well have disembarked there in order to visit her, en route to Sydney, where his dear brother, George, who by then had been in Australia some 7 years, was about to get married.

Back to Kerry

By 1870, then, the Killorglin Hicksons had all left their native land. That same year their father, Richard, who had gone with William and Mary to America, died and was buried in Providence, Rhode Island in the USA. William and Mary remained around the Boston area where another five children were born in the family. However, by 1877, 12 years after they had left Ireland, William and Mary had had enough of the USA, and returned to Kerry, migrating again a few months later to Australia, at the urging of youngest brother John, who was by then doing rather well in Sydney as a timber merchant.

Things had gone wrong for George in Sydney, despite the arrival of his younger brother John. George had married in 1870, as mentioned, the year John arrived in Australia. However, his life was marred by tragedy when first a son, Richard, then a daughter, Lily, died in infancy. Only 6 months after Lily’s death, George died too, aged just 28.

His sister Kate, to whom he had always been closest in the family, was still unmarried, and was heartbroken by the childrens’ deaths. Wondering what life could hold for her, a 29 year old spinster, she tool the long voyage back “home” to Ireland, only to realise, after s short sojourn, that she no longer belonged there, and that there could be no future for her in the land of her birth. Boarding a ship she sailed back to Australia, and on board met a Scotsman who would become her husband.

The youngest Hickson, John, who was financially the most successful of the Hickson family, and therefore had the resources to travel for pleasure, returned to Kerry several times during his long life, the first time in 1893 with his oldest daughter, Alice, and twice more in the twentieth century. His story will also be the subject of another blog.

Remains of the day

Today nothing remains of the Hickson family in Killorglin – well almost nothing. On one of his journeys back to Killorglin in 1911 John Hickson placed a plaque in the lobby of the old Church of Ireland church in Killorglin, a building which is now a cosy Spanish restaurant. The plaque remains there to this day and reads:

Just sending you this from the KENMARE CHRONICLE about the CARTER Sisters of Kenmare. Have some pics too if you are interested. No Carters left in Kenmare now but there is still a relation in Killarney I think.

Simon Linnell, Editor.

THE CARTERS OF MARKET STREET.

by Honor FitzGerald.

The story begins in 1901 when Nathaniel Carter married Ellen Freeman. Nathan at that time was living in Bridge Street and they lived there for the next ten years or so before moving to 26, Market Street.

While they lived in Bridge Street they had three children. Their first child, James, who was born in 1901 died in infancy. The in 1903, Hannah was born followed in 1905 her sister Nell.

Nathan was a ‘Bootmaker’ by trade and carried out his work in Bridge Street initially and continued when they all moved up to Market Street. Ellen Carter worked in Clifford’s’ Bakery in Henry Street as a housekeeper for William and Kathleen Clifford.

Mrs Carter, Hannah and Nell were wonderful and caring ladies. When Mrs Clifford from the Bakery died the youngest of the family, Kitty, was only 9 months old and to help out she brought her back to her house in Market Street where Hannah and Nell could help look after her. Mrs Carter continued to help out in the Clifford’s home. It was a wonderful and thoughtful of Mrs Carter to help them out in this way.

Hannah became a seamstress and Nell worked as a cook for Dr Moore in Bell Heights, Kenmare.

Kitty, when she grew up, married Michael FitzGerald from Tralee and she was the mother of Ted, Honor (that’s me!) and Kay. Hannah and Nell loved to come and visit us in Tralee especially at Christmas time. They would arrive with the Turkey, plucked by Nell and ready for the oven, her homemade Christmas cake and a ‘Christmas Brack’ from Cliffords…and of course presents for all of us! We would be so excited. Christmas with Hannah and Nell was wonderful. We loved having them. They were so kind and caring to us as a family.

When we would visit Kenmare we would always stay with them in Market Street. The ‘slippery rock’ and ’Cromwells Bridge’ were the places we wanted to go to on our trips and Nell always brought us there. A visit to ‘Ladys Well’ was always on our walks and a few pence each to spend in Janey Sheehans shop at the end of each excursion. We would always be so lonely leaving. As I grew up I was able to stay with Hannah and Nell during my summer holidays from National School. It was a special time in my life. They took great care of me, our walks, picking flowers, slippery rock, the pier and visiting their friends are loving memories. I continued to stay with them for the summers during secondary school.

Then in the 1960’s, like completing a full circle, after leaving school, I came back to Kenmare to work in Clifford’s bakery. I would call to Hannah and Nell every evening after work for a cup of tea and a chat, discussed my news and the happenings of the day which they loved to hear. If they needed jobs doing like going to the Pump for water or getting the shopping I would help.

Hannah and Nell were lovely ladies and always looked very stylish. Hannah was a very popular Dressmaker and the busy time for her was always around the First Communion and Confirmations making dresses and coats for the children. Costumes for St Patricks’ night concerts and Fancy Dress parties would also be produced. People from all around the Kenmare District for Hanna to do renovations or make new clothes. They were always welcoming visitors to their house and you would be asked to sit and have a cup of tea and a cake…and enjoy a bit of a chat.

Nell was the cook in the home and always prepared the meals and baked bread and cakes, all on an open fire. I still remember well, sitting beside Nell when she was making bread and cakes and my fingers stuck inside the bowl!

Wonderful and beautiful memories.

Both Nell and Hannah were members and very much involved with the Irish Countrywomen’s Association (ICA). They would go away on all the outings organised by the ICA and would enjoy them thoroughly returning with loads of stories to tell to a listening ear.

The Corpus Christi procession was very important to Hannah and Nell and they were always involved with the Children of Mary. They would also help to maintain ‘Our Lady’s Well’, planting flowers and cleaning the area. Over the years there would be many a time I would have helped them with this task.

Nell loved doing Crosswords and would do them every day. There was also a deck of playing cards always on the table. In the evenings we would sit by the fire doing basket weaving, embroidery and patchwork. Hannah and Nell would always be encouraging me to learn different things. After awhile I could do my own embroidery patterns and patchwork designs which I now have hanging on the walls of my own house.

The radio was always on in the house as they loved music. One particular programme they both loved was the ‘Archers’ and you had to sit in silence during the programme or learn not to call at all at that particular time.

Rose and Robbie Gaine, neighbours from across the street in Emmets Place were always there for Hannah and Nell, helping in any way they could.

Nell died in 1971 and when Hannah died in 1980 I was in America and I was very upset and heartbroken that I was not there for her. Both Hannah and Nell were wonderful people especially to my Mum and Dad, to Ted, Kay and myself. They became part of our extended family.

Beautiful memories, never forgotten and always in our prayers.

Thanks a million Simon!