The following is the first of a series of three articles.

At the end of 1856 a family of seven named Anderson from Stirling, Scotland, arrived in Sydney in the colony of NSW, after a 3 month voyage around the world. Eight months later two more Scottish immigrants arrived at the same port, a brother and sister, Helen and Andrew Ross. Before they came to Australia the Rosses had no knowledge of the Andersons. But on the far side of the world, in their new home, their lives became forever entwined.

The Andersons, a family from Perthshire

William and Ann Anderson sailed with their five children on a ship with the unlikely name of Edward Oliver, out of Liverpool in August, arriving in Sydney on 22 November 1856. On the arrival papers William, and his eldest son, David, aged 14, are listed as farm labourers from “Laggie” in Perthshire. The other children, Janet, William, Isabel and James, are all listed as “students.” There is no town named Laggie in Scotland, but just north of Stirling over the River Forth (and just north east of the present day University of Stirling) there is a parish called Logie, (see on google maps) which “derives its name from the Gaelic word lag or laggie, denoting “low or flat ground,” the lands consisting principally of an extensive tract of perfectly level country.” The foreboding Stirling Castle high on its rocky crag had always been a familiar landmark for the Andersons, but as the train for Liverpool carried them south in the summer of 1856 the old fortress disappeared behind them, to become little more than a fading memory for the rest of their lives.

The Rosses, siblings from Ross-Shire

Hundreds of kilometres north of Stirling another Scottish family was also talking about migration. Sister and brother, Helen and Andrew Ross, respectively 27 and 23 years old, had, like so many of their countrymen, decided to go to Australia too. The Ross family home was located in Gledfield, a small village near Ardgay, (see google maps) a day’s journey north of Inverness, at the mouth of the Strathcarron, in the eastern Highlands. Eight months after the Andersons had embarked on their voyage, Helen and Andrew also sailed out of Liverpool, leaving in April and arriving in Sydney on 23 July 1857 after a voyage of 91 days on a sailing ship named Alfred.

They were not the first of the Ross family to leave the village, but they were first to leave Great Britain. An older brother, James, had left home some ten years earlier when he was just a teenager, making his way to England where he met a girl from Wales, Mary Ann Marston, whom he married in 1853. They had settled in Wales, near Mary Ann’s family in Welshpool, where their first child, Alice, was born, but had moved soon after back across the border to the English town of Birkenhead, just across the River Mersey from Liverpool.

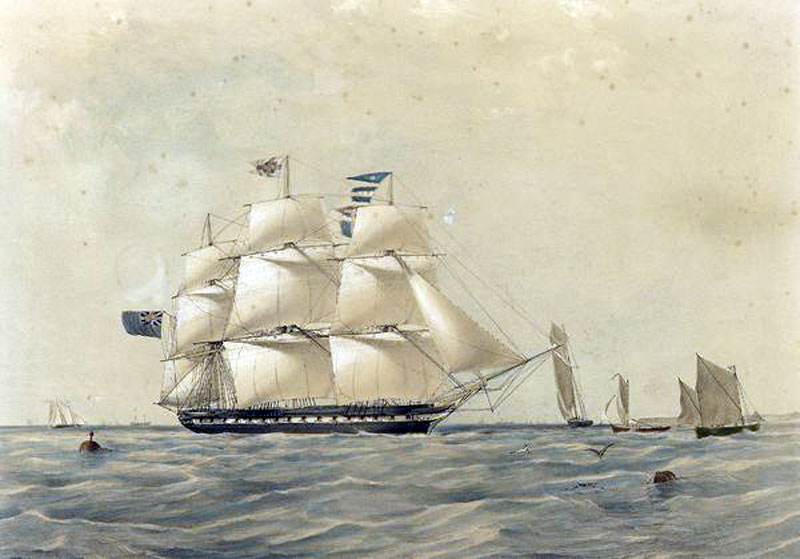

Andrew and Helen, leaving the still snow covered hills of Ross-shire in the Spring of 1857, presumably travelled first by horse drawn coach to Inverness (the Inverness to Aberdeen railway was still under construction), then by train from Inverness to Liverpool where they were met by James and Mary, before crossing the river by ferry to the Ross home in Birkenhead. The young siblings, who had grown up in the relative remoteness of the Scottish Highlands, were overwhelmed by the sight of literally hundreds of ships, arriving, leaving or moored at the many docks along each bank of the wide river. Liverpool had become the biggest migrant port in England by the mid 1800s, the river crowded with the masts and sails of merchant/migrant ships, as well as the steam tugs, supply punts and ferries that serviced them. The city itself was flooded with people from all over Britain and Europe, since even migrants from Europe – especially Germany and Scandinavia – made their way first to Liverpool before departing on their voyages to the new worlds of America and more distant destinations like Australia.

Birkenhead, though not as frenetic as Liverpool, was nevertheless a rapidly growing Victorian town, and had been a good place for a young journeyman joiner like James to establish his business. He and Mary were glad to welcome his younger siblings, Helen and Andrew, into their home on Watson Street. It was close to a decade since James had left the Highlands, so there was plenty to catch up on. They could not help being captivated by the tangible excitement of Helen and Andrew as they enthused about the new lives they would build on the far side of the world in the young colony of New South Wales. James’ wife Mary was pregnant with their third child, so they too were filled with anticipation about the changes ahead of them. The baby arrived, as it turned out, 3 months after Helen and Andrew left England, around the time James and Mary knew that the siblings would be arriving in Sydney. To honour that arrival they named the little boy Andrew, for his adventurous uncle.

Leaving the “old country”

Why were so many people leaving Britain in those days? The old country seemed to be happy to be rid of them, and the fledgling colonies of the British Empire were crying out for settlers. The Andersons and the Rosses were “government immigrants” according to the shipping notices in the Sydney Morning Herald, which meant their fares were subsidised by the Australian government. The colony of NSW was at that time sorely in need of a labour force, especially after the end of convict transportation to the colony in 1842.

In Britain, on the other hand, there were more people than jobs. Economic forces and an unsympathetic landed aristocracy in Britain were driving many, especially in Scotland and Ireland, off the land that had been the source of their livelihood for generations. The Strathcarron – the Highland valley where the Rosses lived – had been the site of repeated “clearances” since 1792, so the population was shrinking, the landowners keen to replace the people with sheep, which were to their mind more profitable. The Gledfield Ross family were not tenant farmers, so were not victims of the evictions, but there were thirteen children in the family who all had to find livelihoods, which was becoming increasingly difficult as the population shrank. Although Ann, the oldest sister, had married a blacksmith from nearby Edderton in 1849, and remained in the area her whole life, James had decided to leave Scotland, moving south to England to build a life. Another older brother, John, would eventually join him in Birkenhead.

But Helen and Andrew were prepared to go even further, and taking advantage of the substantial government subsidies, had booked tickets to New South Wales. Andrew listed himself as a “farm labourer” and Helen as a “farm servant,” which were just the sort of skills that the colony was looking for. The Rosses were not really a farming family – their father back in Gledfield was a blacksmith, and several of his sons, including Andrew, had learnt that trade. But Gledfield, Ardgay, the Strathcarron, were all farming communities, and working on the land was in their blood.

The Andersons were similar to the Rosses in the sense that William had listed himself and his oldest son, David, as “farm labourers” when he applied to migrate, though the 1851 Scotland census had listed him as a woollen weaver, so he was not exactly a farmer. However, he knew that there were ample opportunities in the new colony for people prepared to work hard on the land, and there was also the dream of owning his own farm, something that he could not even imagine in Scotland, but which, according to the advertisements he had been seeing in the papers, was something quite within the reach of anyone willing to make the long journey to Australia.

Sailing to Australia in the 1850s

What was the 3 month voyage like for immigrants to Australia in the 1850s? A newspaper article describing a voyage of the Alfred around the same time to Australia gives a good idea of what it was like for the Ross’s journey, and the Andersons voyage on the Edward Oliver cannot have been much different.

This Moreton Bay Courier article was written after Alfred arrived in Brisbane in September 1858. I have included some comments in [brackets]:

There was… delay on the part of the authorities at home [in Liverpool] in despatching the vessel from the River Mersey… The Alfred was towed by a steam-tug until off Tuscar [presumably Tuskar Rock, Ireland]…, [after which she] began business on her own account… In 30 days the “Alfred” made the Line [presumably the Equator]; and the winds she fell in with up to this time cannot be spoken of as favourable. The vessel passed through the Tropics without the passengers suffering more inconvenience than might have been anticipated. In 60 days the latitude of the Cape of Good Hope was made; and about this period of the voyage the vessel suffered ten day’s adverse winds. The only land sighted on the voyage were the Isle of Trinidad – Rocks of Desolation.

The number of births on board was 5, and the number of deaths 4…

The passage was in every respect a favourable one. Lectures were delivered on various subjects. Entertainments of vocal and instrumental music were given ; the votaries of terpischore also delighted to trip the light fantastic toe. A mock trial – and a mock execution also took place – the particulars of which will, some other time, form an interesting tale, with which we shall gratify our readers. Before the Commissioners there were no complaints from the passengers, a fact almost unprecedented in the history of immigration.

Nor must we forget to mention that the religious exercises were not forgotten. Mr. Cumming, the schoolmaster, read prayers regularly, weather permitting; and gave also religious discourses in various parts of the ship, to those passengers who desired to hear of the way of life. The general conduct of the immigrants was good. The major portion of them had been worthy honest labourers at home ; and spoke of work as the ” one thing needful” for bettering their condition.

It was remarked by a gentleman of colonial experience, who saw the body of immigrants previous to the commencement of the hiring, that it was rarely so respectable a number was seen together. There were English, Irish, Scotch, and Welsh; while the subdivisions were — principal portion from the West of England, Somerset, the majority of the passengers English; next in ratio Scotch, the Irish were the next numerous ; but the Welsh might be numbered under a score.

Moreton Bay Courier (Brisbane, Qld), Saturday 2 October 1858, page 2

So the three month voyage, though it consisted of many tedious days staring out to sea, was punctuated by all these kind of events, the stuff of life – lectures on various subjects, school lessons for the children, births and deaths, church services, interesting landfalls, the obligatory “crossing the line” ceremonies and musical entertainments. There was no doubt much swapping of stories between passengers, and endless planning and dreaming of the new life that awaited the migrants in Australia. Although the voyage described sounds idyllic, it would be unrealistic to imagine that it was all “plain sailing.” In a crowded ship there were surely also petty arguments and rivalries, gossip and the tensions that arise from months at sea at close quarters.

The reference to Trinidad in the article above was surprising to me, since it is on the other side of the Atlantic to where they were going, but the following description from the State Library of South Australia website was enlightening:

The route sailed [by migrant ships to Australia] didn’t change very much until the last decades of the 19th century: the English Channel and the Bay of Biscay, both with their notoriously rough weather had first to be negotiated whether the ship was sailing from an English or a Hanseatic (German) port. Once the tropics were reached the weather improved, providing more opportunity for the passengers to enjoy the open air, but if the ship was trapped in the doldrums, it would be many weeks of windless air and heat, and a monotonous heaving sea that had to be endured; tempers frayed and violence could ensue.

Delays in the doldrums also placed a strain upon provisions, especially water. The ship might be forced to call at Rio de Janeiro, or Cape Town to restock.

Whatever the fortunes of a quick passage, or slow, once through the tropics the ships always steered well to the west in the south Atlantic, towards the South American continent, in order to pick up the winds and get below South Africa and then find the Roaring Forties, which would take the ship speedily across the Indian Ocean to its Australian landfall. High seas were a feature of these latitudes and icebergs might be seen, or worse encountered, if the captain steered too far south. There are records of ships being damaged in the winds, but not of ships being lost. Worst for the passengers though was that usually the hatchways would be battened down in the high seas – this made conditions below decks uncomfortable in the extreme.

(State Library of South Australia website)

See map on this page for a general idea of the route taken

In the next article in this series of three I will describe more of what awaited the emigrants when they arrived in Sydney

Hi David,

Another interesting story – with some similarities to my Scottish side. Though not related to yours, my Scottish maternal great grandmother was Ann Anderson, her parents being James Anderson and Elspeth Benson. My Ann Anderson was born in Canada, where presumably her parents had emigrated. At age 12 she appears on the Scottish census as a boarder in a house in Dundee. I know her father died and family gossip has poor Elspeth turning to the bottle. Ann married George Lawrence who appears to be the illegitimate son of Andrew Lawrence/ Lawrance and Margaret Kinloch. This may have been an “irregular marriage” or a “marriage by declaration”, because Andrew acknowledged George as his child (his first wife died). The other odd thing is that George Lawrance had a connection with a family called Ross. It appears that the Ross family may “have taken George in” as a child. (His mother appears to have been somewhat challenged). My grandmother, George and Ann’s oldest child wrote to Finlay Ross for many years and I have some of the letters he wrote to her. In many he calls her ‘dear cousin’ and in one he mentions ‘the war’ which from the date would appear to be the second Boer war. Finlay sounds a bit pompous, but his letters are an interesting insight to life in the late 1800s.

Sorry ….. no good sending it to me if you don’t want me to proof read ….. in your para between the picture of Birkenhead and the picture of Liverpool docks , last sentence you have a redundant ‘new’. This should not be viewed as critical appraisal. I have really enjoyed a bird’s eye view into other parts of your family and I am in total awe and admiration that you can find the time to research. I have not done any family history much for ages, life getting in the way. I do need to get the Lawrance/Anderson family fit for sharing as two of my cousins (sisters) have been given the dreaded vascular dementia diagnoses. One has been in decline for a few years, the other is only recent. This is also the line of my family with seven members developing ca breast.

Not all is gloom and doom though, I will hopefully have a new kitchen before year’s end ad I have planned a short sojourn to Cape Town and Johannesburg including 3 days in Kruger National Park for the end of next October. Long term planning comes with discount pricing.

Best wishes, and thanks for the Scottish connection.

Barb

Sent from my iPad

Thanks for reading Barb. And correcting. I have duly updated the post. Your Anderson family is very complicated. You are so lucky to have letters. I have so little to go on. I imagine things, but I am not very good at creative writing. Otherwise I would write a novel. But I do like writing these little histories, and I think it is worth the time it takes. My Ann Anderson dies in the next episode. We are also fixing up our kitchen. Just a cosmetic makeover but these things are still so costly. You should drop in one day when you’re heading up the valley.

Hello David, I am a descendent of both the Anderson and Ross families and very interested in your story. I would like to get a copy . Kind regards Esme.

Hi Esme, so good to hear from you. Remind me of your family tree. I know your name of course but I can’t remember the details. My own Ross ancestor was James Ross, who never left the city. Somehow I imagine him to be less adventurous than Helen and Andrew, but maybe, being older, he had just run out of steam, and after travelling around the world he just wanted to settle. He gets a mention in the next blog in this series. Good to hear from you. Any family stories you would like to share are welcome. Best wishes, David