This is the sixth and final essay in my series of blogs on my family’s involvement in the Church of Ireland in County Kerry. It is about the revival that occurred in 1861 and the foundations of the Plymouth brethren. It is a long read, allow 15 to 20 minutes.

My Irish Brethren great grandparents

When I was young I became aware that my maternal grandmother (born Gertrude Byrne) grew up in a Brethren family. I had very little idea what that meant, except that it was a rather austere form of Christianity, which seemed to be characterized by a lot of things you weren’t allowed to do. Gertrude Byrne, who became my “Nanna Simmonds,” was a gentle soul who I remember primarily for her relative poverty. She lived far from us and died when I was 14 years old, so I can’t say I knew her well. Her husband, my grandfather, died before I was born so I didn’t know him at all. Even when he was alive they were poor. George Simmonds was a migrant who had come over from England between the wars, but his only skills were those of a market gardener, and here in Australia he ended up an itinerant farm labourer, and then there was the Great Depression. George, however, was not from a Brethren background.

They married in 1933, when poverty was still the norm in much of the Australian bush, where he worked. Years later, when the family was still young, a fall from a horse, which rolled on him causing internal injuries, left George Simmonds with chronic health problems which plagued him until his death at age 50 in 1955. In those days, before Worker’s Compensation existed, Nanna Simmonds was left a poor widow. She never seemed to possess anything much, always lived in rented accommodation, with minimal furnishings or possessions. But she was a woman of strong faith who read her Bible faithfully and prayed for her children and grandchildren fervently. Her great desire was they would find that same faith that had sustained her through a difficult life. In my case, at least, her prayers were answered.

Gertie left the Brethren church when she married. Her English husband was Church of England, something that did not impress her parents. Gertie and George Simmonds chose not to worship according to either Brethren or Anglican tradition, but rather joined the Baptist Church in Goulburn, which was something of a compromise for both of them. But the Baptists of the 1940s and 50s when my mother and her sisters were growing up were every bit as strict as the Brethren. No movies, no dances, no smoking or drinking. And no doubt the dress code was very conservative.

Gertie’s parents (George and Susie Byrne) were staunch Irish Brethren. Susie had arrived in Australia first, with her parents, when she was 16. George came alone in around 1882 when he was 22. They had known each other in County Kerry as children, but they married in Australia in 1885. They remained faithful adherents to Brethren ways from the time they married until their respective deaths in 1929 (George) and 1945 (Susie). Of their five daughters, three remained spinsters and Brethren all their lives. Gertie left and joined the Baptists as mentioned. The other, Connie, became an Anglican, much to her parent’s horror. Their only son, William, had little time for religion, according to later reports. I have little knowledge of his life, except that he was a veteran of both world wars and died in Queensland. As far as I know he had no children.

As I have discovered more about my Irish “religious” heritage, questions have naturally arisen: what was this Christian movement coming out of Ireland in the nineteenth century that became known as the Plymouth Brethren, and later just “Brethren”? I knew my maternal great grandparents, George Byrne and Susie Hickson, were Irish Protestants, but as far as I had known they were both baptised in the Church of Ireland in Co Kerry. Where did the Brethren movement fit into the Protestant religious mix in this deeply Catholic county? And how did the Hicksons and the Byrnes end up being part of it?

The answer, of course, is that Susie Hickson’s and George Byrne’s parents were witness to the Kerry Revival of 1861, the year of Susie’s birth. This revival happened within the Church of Ireland, but as often happens at such times, those who experience such a fresh outpouring of the Holy Spirit grow disillusioned with the religious tradition from which they come (often blaming that tradition for their previous spiritual dryness) and express their new found enthusiasm by forming new Christian movements. The Kerry Revival was fed by the teaching of Brethren evangelists from Dublin, and it was natural that the people largely rejected the established Church of Ireland to form new Brethren assemblies.

The 1861 Kerry Revival

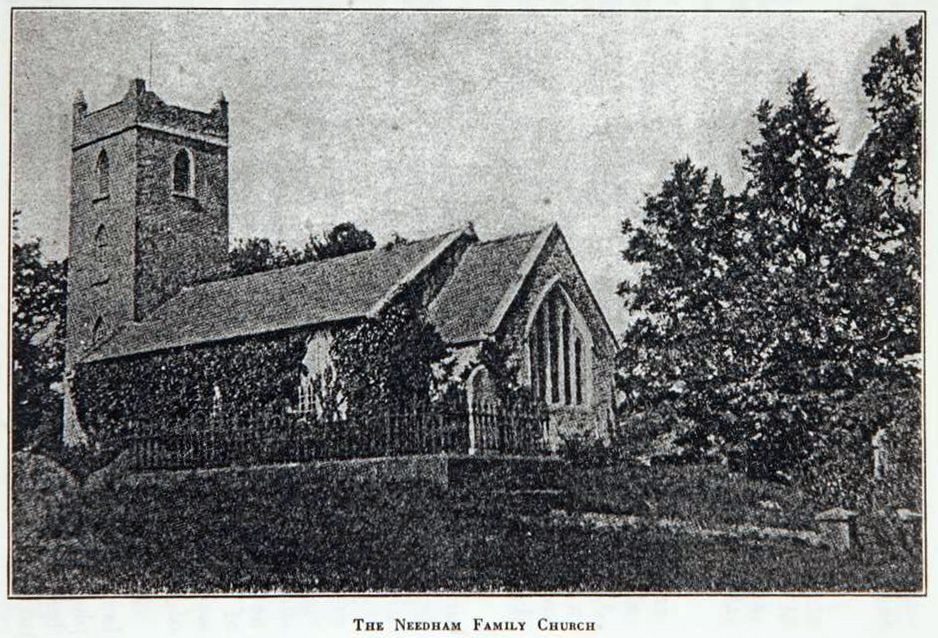

The Kerry Revival began in the little village of Templenoe, between Kenmare and Sneem on the Iveragh Peninsula, which was Mary Needham’s hometown. Mary had married William Hickson of Killorglin in 1858. Susie their first daughter was born in 1861, the year the Revival broke out in Kerry. The Needham family in Templenoe were at the epicentre of the Revival, which quickly spread through the COI congregations in Sneem, Killorglin, Killarney and further afield. My ancestors came from four families all of whom appear to have been affected by the Revival: the Needhams in Templenoe, the Hicksons in Killorglin, the Byrnes and Ruddles in Killarney.

George Byrne’s parents, George Byrne (senior) and Sarah Ruddle, were close friends of Susie’s parents. The Byrne family lived in Killarney, where they had close connections with the Church of Ireland in Killarney and Aghadoe, but they too left the COI and joined the Brethren movement following the Revival, perhaps influenced by their friends the Hicksons. George senior had been baptised a Catholic and appears to have converted to Protestantism before his marriage to Sarah Ruddle. Their first two children were baptised at the Aghadoe COI, but when George junior was only a toddler George and Sarah left the COI and joined the Brethren movement. So all the Byrne children, including George, were raised in Brethren ways from an early age. George and his brothers would take those ways with them when they successively migrated to Australia.

The Hicksons for their part, though very much a part of the Brethren movement, migrated to the USA in 1865 when Susie was 4 years old. In America they attended mostly Methodist churches, since it would seem that the Brethren had not really become established in America at that stage, although DL Moody, the great American evangelist of the late 1800s, was very influenced by Brethren teaching. The Hicksons left America (and all their Needham relatives, who had migrated there) in 1877, returning to Ireland briefly before migrating again, this time to Australia (where the wider Hickson family had all migrated). Susie was 16 by that time and it would seem that the Hicksons reconnected with Brethrenism in Australia.

George Byrne did not come to Australia until 1882, when he was 22. Despite his baptism in the Aghadoe COI, he had been Brethren all his life, and carried strong convictions about the truth of Brethren teaching. Married to Susie in 1885, he was the guiding religious force in the family they built together. This was the family into which my grandmother was born in 1900.

The Brethren movement in Ireland

The origins of the Brethren movement in Ireland predated the Kerry Revival of 1861 by some thirty years. “Brethrenism” was not, therefore, a result of the Revival, but it did become the practical expression of the spiritual awakening which the Revival sparked for many in Kerry.

The Revival broke out among the Protestant population of Kerry two years after a similar revival in the Presbyterian Church of Northern Ireland, and was no doubt viewed with skepticism and suspicion by the Catholic majority, resentful as they were toward aggressive Protestant proselytism in previous generations. Any spiritual fervour amongst Protestants would probably have been seen as a threat, a possible prelude to more attempts to convert Catholics. The fears of the Catholic majority, however, were largely unfounded, since this new spiritual movement was not so much about proselytism towards Catholics as it was about renewal amongst Protestants. The few Catholics that did convert were more likely persuaded to do so by the change they saw in these Protestants, rather than forced to do so by any action of the Anglo-Irish aristocracy.

“Brethren” was never meant to denote a denomination, though in many ways it became one as the years unfolded. The “Brethren” wanted to be known only as Christians, and not be labelled or connected to any particular denomination or sect. However, they became a distinctive group. Tim Grass, in his recent study of Brethren history, Gathering to His Name, briefly describes the designation “Brethren” as

referring to an Evangelical movement of spiritual renewal which began in Dublin and the South West of England (hence the term Plymouth Brethren) around 1827-1831, … which had as one of its main concerns the realisation of a fellowship in which all true believers in Christ might find a welcome. The pioneers sought to be open to the illumination of the Holy Spirit concerning the teaching of Scripture, placing no credal or tradition-based restrictions upon where obedience to God might lead…

(Grass, p.3)

The beginnings of the movement were the result of the convictions of various “Evangelicals” in Ireland (Anthony Norris Groves and John Nelson Darby were key figures), and their contacts in England and Scotland. The label “evangelical,” now so often associated with negative political connotations, refers essentially to a belief in the Bible as accessible to all people and authoritative as a guide for spiritual, intellectual and physical life. A number of future Brethren leaders were students at Oxford during the 1820s, so there was a strong intellectual foundation for the ideas and teachings of the Brethren. Notable individuals among the early Brethren were the Irish dramatist JM Synge, the Scottish evangelist Henry Craik, and a German, George Müller, who had come to England for missionary training but ended up starting an orphanage in Bristol which became famous in the years that followed. All of these had become disillusioned with the Church of England (which in Ireland was known as the Church of Ireland), all of them had experienced dramatic conversions of one sort or another, sometimes within the context of training for ministry, and all of them came to question various aspects of the established church.

Perhaps one of the distinctive features of the movement was that all Christians were seen as equal in their ability to hear what God was saying, regardless of their level of theological education. Groups of believers met in one another’s homes, or in community meeting halls, without any specific leader, priest or minister – Brethren denied the necessity of ordination to hear and interpret God’s voice in the Scriptures, or to administer the sacraments of Communion, Baptism and the like. In meetings anyone was allowed to “bring a word” from God that they felt the Holy Spirit had impressed upon them.

The Anglo-Irish gentry and the Brethren movement

One of the interesting characteristics of the early Brethren was their political conservatism – despite world-denying attitudes, and their belief in equality before God, they were far from being political or social radicals (Grass, p86). They tended to see the status quo as being God ordained and in no way attempted to dismantle the hierarchical arrangement of British society. It is not surprising therefore that the gentry were comfortable with this form of Christian spirituality, but that it rarely appealed to the more revolutionary parts of Irish society for whom the number one priority in creating heaven on earth was to rid themselves of the British imperialist ascendancy.

Traditionally, the Anglo Irish gentry were members of the Church of Ireland, the establishment church. But it was no secret that this particular church, at the same time as being a Christian denomination, had been used as a political tool by the British government for hundreds of years, part of the machinery the English had used to attempt to subdue the native Irish population. Although some gentry no doubt felt quite comfortable with such a strategy, others were distinctly uneasy with the knowledge that religion should be used as a political weapon. For them, spiritual convictions were matters of the heart, the conscience, personal, not political. Certainly they were keen for their “non-believing” neighbours (most of whom happened to be their Catholic tenants) to discover and adopt their Protestant faith, but they were not prepared to bully them into it, even if the British government was.

One such gentleman was Richard Mahony, the landlord of Dromore Estate, which encompassed the town of Templenoe where the Needham family lived. Susie Hickson’s mother was Mary Needham, first born of George and Susan Needham’s ten children. George was the Templenoe parish clerk and knew Richard Mahony well, though he was contemporary with Richard’s father, the Rev Denis Mahony. Denis had been a Protestant clergyman and notorious proselytiser and was widely disliked in the area. But Richard himself, who took over the estate after his father’s death, was very different. Although he was the patron of the local Templenoe COI (of which he remained a member all his life), he was affected by Brethren ideas and began to hold meetings in his house, Dromore Castle, for the local people, which Brethren speakers were invited to address. The 1861 revival was sparked by these meetings.

One of the first to be affected was Mahony’s neighbour and childhood friend, FC Bland, of Derryquin Estate near Sneem. I believe that Mary‘s husband, William Hickson, and his good friend George Byrne, may have both worked as nailors on the Bland estate, prior to William and Mary’s marriage in 1858.

TS Stoakley, in his book, Sneem, the Knot in the Ring, writes of the effect the Revival had on FC Bland (Frederick Christopher Bland)

JF Bland died in 1863 and was succeeded by his eldest son FC Bland… but two years before his succession something had happened which was to have a profound effect on the destiny of Derryquin. This was the formation in Kenmare of a religious revivalist sect whose members were usually simply known as Brethren, although the remnants who survived to record their religious affiliation in the censuses of 1901 and 1911 gave it as Plymouth Brethren. One of the gentry of the area, Richard Mahony of Dromore Castle, which is about halfway between Kenmare and Derryquin – became converted to their beliefs, and he in turn passed on his convictions to his great friend Francis Christopher Bland. The sudden change which took place in the latter’s priorities was thus expressed in his obituary:

It was the year 1861, and while busily engaged in the improvement of his estate and the condition of the tenants thereon, by building, roadmaking, draining, that the revival broke out hard by in the meetings held by his dear friend and neighbour the late Mr Richard Mahony, of Dromore. Becoming anxious about his salvation, in the presence of numerous conversions among his acquaintances, he consulted the Rev Frederick Trench, of Cloughjordan, the well known founder of the Home Mission, and from him received the strange advice to begin preaching, and as he said, “in watering others you will yourself be watered.”

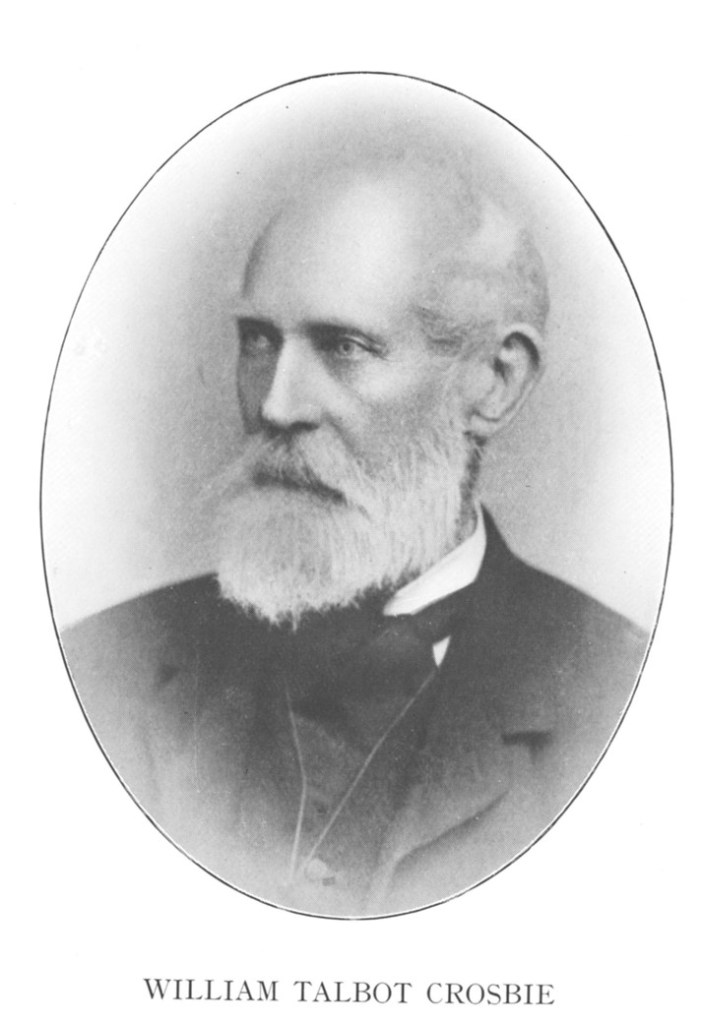

The response of FC Bland to Frederick Trench’s advice is recorded elsewhere. A short biography of Frederick Trench himself is to be found in Henry Pickering’s Chief Men Among the Brethren, which explains that he married a Miss Talbot-Crosbie and made his home in Abbeylands, Ardfert, Co Kerry, from where he conducted his ministry. A relative of Miss Talbot-Crosbie was another Kerry landlord, William Crosbie, who was also converted to Brethren ways. Pickering’s Chief Men is glowing in its description of William Talbot Crosbie, but other accounts of this particular landlord are less positive. For example Michael Keene writes in a recent article:

Along with a couple of other leading landlord families, they dominated Kerry politics throughout much of the 18th and 19th centuries, representing the county almost continuously in Parliament, firstly in Dublin and then in Westminster, for much of that time. When elevated to the rank of Earldom, the Ardfert Crosbies, as Earls of Glandore, lived in great style for a time both in Kerry and in their fine Dublin townhouse, now Loreto Hall, on St. Stephens Green. That era led to the long stewardship at Ardfert of William Talbot-Crosbie, or ‘Billy the Leveller’ as he became widely known, from 1838 to 1899. While he was an innovative agriculturalist, his extremely harsh treatment of tenants which included widespread evictions and his activities during the Great Famine remain highly controversial to the present time. Remarkably, ‘Billy the Leveller’s’ successor at Ardfert Abbey, Lindsey Talbot-Crosbie, supported land reform and Home Rule, while his son in turn Maurice was a candidate for the Irish Parliamentary Party in Cork in the 1918 general election.

It is hard to reconcile the very positive Brethren description of Crosbie with this description of his “extremely harsh treatment of tenants” but that seems to be the legacy for which he is most remembered in Kerry, and which no doubt contributed to the destruction of his Kerry home, Ardfert Abbey, during the War of Independence in 1921. However, other descriptions of Crosbie’s activities in Kerry, not written from a Brethren perspective, are more positive. For example

Crosbie was known as ‘Billy the Leveller’ on account of his re-organization methods. However, Trench (not the same as the Trench mentioned above) wrote that William Crosbie’s cardinal rule in these operations was that no tenant should be removed from his farm unless another was found for him on the estate. (See the discussion of Crosbie and Mahony’s contributions to Kerry society and agriculture and in Richard John Mahony of Dromore, by Murphy and Chamberlain, pp18-21).

Murphy and Chamberlain, p20.

What is clear from all this is that from 1861 onwards the Brethren movement had quite a profound impact on the landed gentry of Co Kerry as well as Protestant commoners and some Catholics. For once spiritual convictions seemed to trump social class. Grass writes, “early Brethren in England and Ireland were perceived as genteel, even well-heeled… Among the early leaders were doctors, colonial judges, retired officers from the services, lawyers, peers, baronets and gentlemen, many of whom were linked by a network of intermarriage, built in part on that of the relatively small Irish Evangelical aristocracy and gentry.” (Grass, p.86) But such members of the upper classes regarded commoners as equals before God.

My direct Kerry ancestors (Hickson, Needham, Byrne, Ruddle) were not landed gentry, although they were related to landowners on the Hickson side. Susie Hickson’s father was a nailor, as was her future husband’s father, George Byrne. But like the network of intermarriage that existed in the Kerry gentry, there was a network of intermarriage within the minority ordinary Protestant population of Co Kerry. Any spiritual movement within this small connected community was bound to spread rapidly in the county and beyond.

What happened to the Brethren of County Kerry?

The two social groups that comprised the first Brethren assemblies in Co Kerry – Anglo-Irish gentry and Protestant commoners – have largely disappeared from the county, and with them the numerous Brethren congregations. With the departure of these small but significant groups, Brethren assemblies gradually dwindled. However, Brethren ideas and ways spread globally through migration, so that descendants of the Kerry Brethren are now spread all around the world.

Protestant commoners, like many Catholics, left Ireland of their own free will in search of a better life with better opportunities. The gentry relinquished their privileged lives in Ireland more reluctantly, driven out by the ultimately successful struggle for Irish independence (as well as the demand for land redistribution) in the first three decades of the twentieth century. The land agitation of the 1800s and resentment toward English colonial rule resulted in intermittent violent insurrections against the aristocracy culminating in the 1916 uprising in Dublin which was crushed, but which heralded the beginning of the end for British ascendancy in Ireland. The War of Independence followed in 1921 resulting in years of Civil War which caused much suffering. Eventually, however, the Republic of Ireland came into being. Only Northern Ireland remained loyal to the British crown.

The Blands have gone, as have the Mahony’s and the Crosbies, along with most of the so called Anglo-Irish ascendancy. During the years of Civil War many of the “big houses” of Ireland were destroyed by republican forces or by angry local mobs. Derryquin Castle and Ardfert Abbey (one of the Crosbie houses) met such a fate, as did the Hickson “family seat” in Dingle (but that is another branch of the Hickson family, and is another story).

The Church of Ireland itself is a shadow of its former self, with churches like the one at Sneem now having only a handful of worshippers on a Sunday morning. This is the same church that in 1860 had to be enlarged to accommodate its growing congregation. The COI building frenzy of the 1800s which saw so many new Protestant churches built in Co Kerry and across Ireland, is now just a memory. Churches like Templenoe and Aghadoe which were once so central to my ancestors lives are either boarded up and derelict or deconsecrated and converted to other uses – residences or restaurants. Some are in ruins or have disappeared completely.

Two local historians (Janet Murphy and Eileen Chamberlain) in Kerry have published a recent (2011) historical overview of The Church of Ireland in Co Kerry, drawing on original sources, which chronicles the rise and decline of the various COI churches in Kerry. They also published the fascinating biography of Richard Mahony of Dromore (2010, revised 2011), quoted above. Interestingly, in neither of these publications could I find any mention of the Kerry Revival. Both are available online as e-books.

In fact, apart from Brethren publications I have found very little information about the Brethren in Kerry. However, Christopher Bland, a descendant of FC Bland of Derryquin, wrote a novel about the passing of the Anglo-Irish gentry in Ireland, Ashes in the Wind, loosely based on his family history, in which the Plymouth Brethren do get a passing mention, though the tone is a little skeptical. The chief protagonist in the story is Henry Burke, whose grandfather is loosely based on the historical FC Bland. He is the subject of the following conversation:

“Henry’s grandfather, High Sheriff of Kerry at the time, converted when the Revival came to the South-West. Joined the Plymouth Brethren and wound up preaching the Gospel in Weston-super-Mare. Why Weston-super-Mare for heaven’s sake? Sent me a copy of his book, he did, Twenty-One Prophetic Papers. Couldn’t make head nor tail of it. Said I could be a brand plucked from the burning.”

Bland C, Ashes in the Wind

Of course, FC Bland is the “Henry’s grandfather” of this story. Bland did in fact write a book by this name, and it can be freely accessed in the Brethren Archives publicly available on the Internet. Other secular references (apart from Christopher Bland’s novel) to the 1861 Kerry Revival I have yet to discover.

The global Brethren movement

The history of the Brethren movement since its earliest times at the beginning of the 19th century is at times inspirational and at times depressing. It was a wonderful movement for renewal within the established Protestant churches in much the same way as other movements like the Methodist societies in England and Wales, the Free Church in Scotland and the Pentecostals in the USA. For over a century Brethren missionaries exerted a very positive influence on the global missionary movement which spread the Christian message around the world.

But at the same time the movement has been plagued by division and controversy since the very early days, as various individuals, striving for purity of doctrine and faithfulness to the Bible, have emphasised one or other aspect of Christian teaching over another. The few histories of the Brethren movement that I have read contain chapter after chapter describing controversies and splits. Even today there are two major branches of the Brethren movement – the so called “open Brethren” and the “exclusive Brethren.”

I grew up in a town in Australia with an exclusive Brethren church on the same street. The windowless church building was surrounded by high fences with locked gates which were opened only when a meeting was in progress. There was no sign to indicate that it was a church, and nothing to indicate that newcomers were welcome. The people who attended were notable for their strict dress code, men always wearing black trousers and white shirts, women always with long dresses and head coverings. A quick search on the internet for Plymouth Brethren brings up an official website, but there is nothing on the website to indicate the specific locations of any of the churches.

My ancestors ended up being members of the “open Brethren” and were presumably less strict than their “exclusive” counterparts. Although some open Brethren groups around the world still use the label Plymouth Brethren, many have chosen other names in order to distance themselves from the exclusive Brethren, which is seen by some as a religious sect. Growing up I was also aware of people from open Brethren backgrounds in the local Anglican churches that my family attended. Such individuals were in my experience notable for their devotion and dedication to God and the Bible, but for one reason or another they had departed from the Brethren assemblies that they had once attended, returning to the “established churches.” Having said that, the Anglican churches in my hometown bear many similarities to the early Brethren assemblies with their emphases on meeting informally in homes and focussing on the supreme authority of the written Word, the Bible, for instruction and guidance on all things. As the open Brethren are less legalistic and strict than the exclusive Brethren, the Anglican churches are generally less austere than the open Brethren, and in that way perhaps more in step with contemporary Western society.

My great grandmother, Susie Byrne, was remembered to have said later in life (after her husband had died) that she wished that they too had left the Brethren when her children were young, because so many of the rules that they had lived under seemed so bizarre and hardly related to the Christian faith at all. Her Anglican friends were much more relaxed. Perhaps her three spinster daughters would have found husbands if they had been less uptight about their religion. Perhaps her one surviving son would not have drifted away from the church altogether if it had been more relevant to the world in which he lived.

References and sources:

Books:

- Stoakley, TS. Sneem. The Knot in the Ring.

- Grass, T. Gathering to His Name

- Pickering, H. Chief Men among the Brethren

- Murphy and Chamberlain, The Church of Ireland in Co Kerry

- Murphy and Chamberlain, Richard John Mahony of Dromore, a Nineteenth Century Gentleman

- Ironside, H.A. A Historical Sketch of the Brethren Movement

- Hambleton, J. Buds, Blossoms and Fruits of the Revival

- Bland, C. Ashes in the Wind.

- Dooley, T. Burning the Big House.

Websites:

Thank you so much for the information on Mary .

Hi Wendy, I am planning to write a blog about William and Mary’s years in the USA. If you have any useful sources, let me know.

Hi David,

re. KENMARE CHRONICLE.

I have just read your new article and found it very interesting. I was wondering if you would be interested in writing an article for us focusing on the Plymouth Breth. just around Kenmare and Sneem. In this years production revolves around ‘Emigration and Immigration’ and a story of the Plymouth Bretheren would fit in well. Would like to include an article along these lines as its part of local history that will soon be completely forgotten. Simon, Editor

Hi Simon, thanks for taking the time to read my rather long article. I have wondered if anyone would really find it of interest. Would be happy to write an article on the Plymouth Brethren in the Kenmare-Sneem area, though I must say I don’t have masses of source material. Maybe you could give me some guidelines as to length (number of words) and deadline, since my time is quite limited at present. Thanks, David

What a mammoth undertaking David. Makes for interesting and informed reading. Thank you.

Great article I never realised the Brethren were in the bones of our families.

I live in the Hills area of Melbourne in the suburb of Upwey .

I have seen members of the Brethren here many times and they do look very different to the norm because of the way they dress . The little head scarf and the modesty of their clothing as they are not showing any flesh . The area up here of Belgrave is where they have a community . Now I feel as if I have a connection to them too ,

.

Thank you as always you are a fountain of family knowledge 😃

Thanks Wendy, it was a challenge to try to get all this information about the brethren movement in Kerry together in one blog. The result was this incredibly long essay which is a challenge to read. I still feel I only have a very superficial understanding of what was happening in those years – the 1860s – in Kerry. It has been a lot of fun to try to imagine those times.